Since Trump Wants to Revive the Redskins, Let’s Talk About Team Names

How celebrating the name behind the Chicago Blackhawks helps us understand ethnic cleansing

Mostly lost in the Pedofuhrer’s most recent assortment of idiotic attempts at human communication has been his insistence that he’ll find a way to bring back the Washington Redskins.

There’s a reason why the name was abandoned. I don’t expect the Orange Puffaroon to have any appreciation for this reason, but I’ll say it out loud anyway. It’s racist.

Luckily, my readers know this. But I’d like to add some nuance to the issue of sports names. To do that, I’d like to introduce you to Chief Black Hawk, a midwestern First Nations dude who is honored as part of the team name of the Chicago Blackhawks.

There is some controversy over the name of Chicago’s NHL sports team. However, there are a few differences between names like the Redskins (or even Braves, especially their hideous tomahawk chop) and the Blackhawks.

The best way to explain these differences is to provide some historical notes that help celebrate the people behind names like “The Blackhawks.”

Consider this an opportunity to take a look at the large number of geographic and civic names in Illinois that are closely associated with the continent’s first settlers, whom I like to refer to as the “First Settlers.” This includes Black Hawk and hundreds of other Native Americans and their cultures.

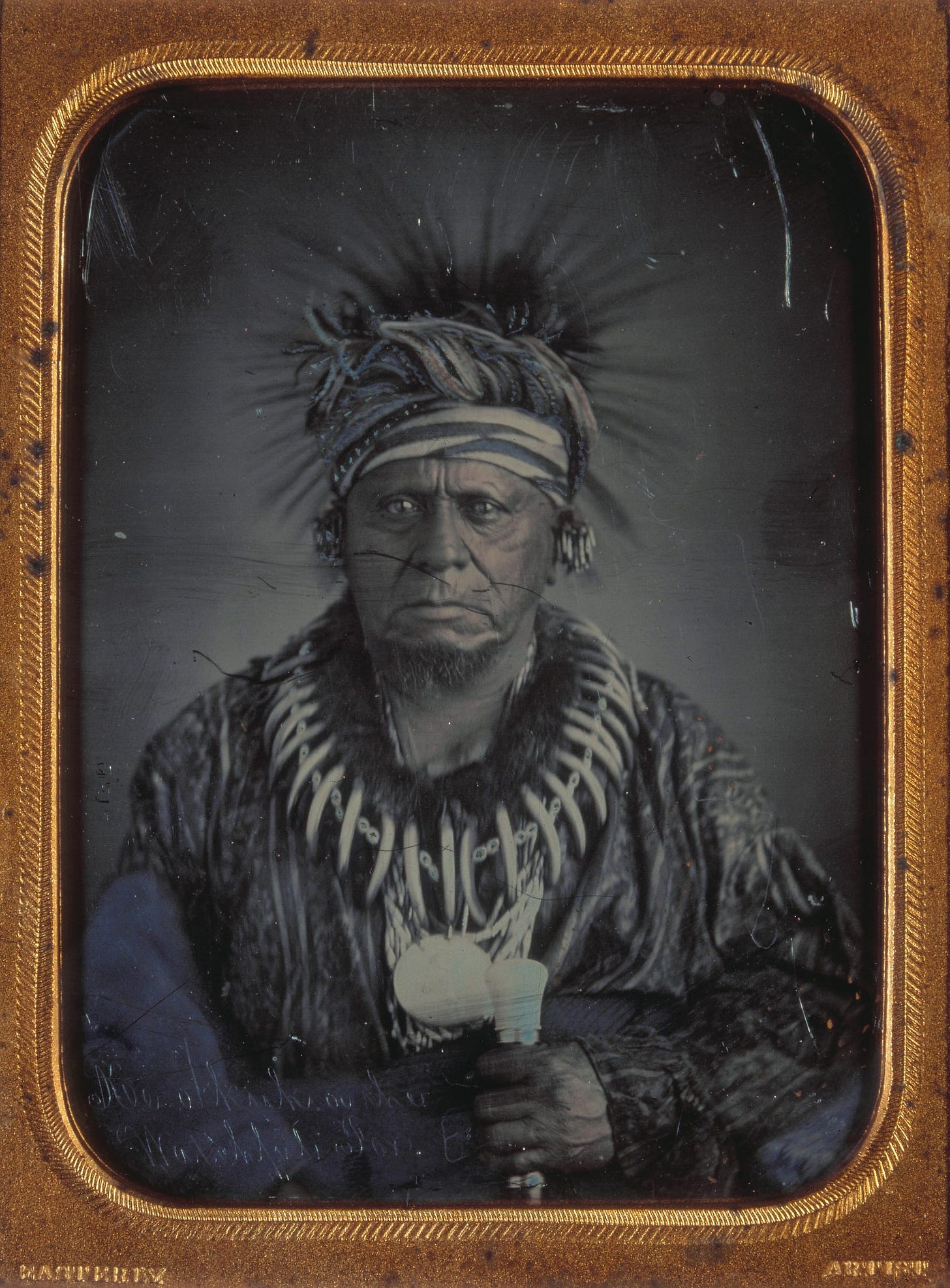

Who or what is a Black Hawk?

Black Hawk was a war leader for the Sauk* nation who lived in the Midwestern United States before the European invasion.

In the War of 1812, Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, aka Large Black Hawk, led a membership drive of sorts among his Sauk nation brethren in an attempt to form an alliance with the British in a desperate hope that it would push white American settlers out of Sauk territory.

It didn’t work. The Americans won, but Black Hawk persisted.

Later, in the 1832 Black Hawk War, he led Sauk and Fox warriors in further warfare against white settlers in Illinois and Wisconsin as the American empire expanded into the West.

Black Hawk was a great American

How do we define a great American? Can an argument be made that someone who hailed from a group of people who lived on the two American continents for thousands of years and led a resistance against foreign invaders was a hero?

The answer seems obvious to me.

Black Hawk eventually became worn down by the superior firepower of his oppressors, but he fought the good fight for a long time before he succumbed.

Origins

The word “Sauk” is a French rendition of the word “Asaki-waki/Oθaakiiwaki”, which is the word the Sauk people used to refer to themselves. “Sauk” was easier for Europeans to say and remember, though.

The Sauk and Fox were both Algonquin in heritage. The Fox called themselves Meskwaki, which meant “people of the red earth.” They were involved in numerous skirmishes with the French while in Michigan.

The Sauk and Fox were close allies, having first been driven out of Michigan by the Attawandaron (aka, Atiquandaronk, referred by the French as “The Neutrals”) and Ottawa nations in the late 18th century. The two nations settled in southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois, as well as Iowa, where they frequently joined forces to fight white settlers.

They settled along the upper Mississippi River between St. Louis, Missouri, and Dubuque, Iowa. By 1800, this range of land was in control of these Algonquin people.

It didn’t last long. By 1804, they were beginning a decades-long retreat to Oklahoma.

Black Hawk Grows up Along the Mississippi

Black Hawk was born in 1767 in the village of Saukenuk, which today is occupied by the Illinois town of Rock Island (currently 0.28% Native American) on the Mississippi. The Sauks had established that town only about 15 years prior, most likely as refugees from the Fox Wars of 1712–1733, which was a conflict between Native American Algonquin-speaking peoples and the French in the Great Lakes region of Michigan.

Between the ages of 15 and 19, Black Hawk participated in battles against the Osage and Cherokee. When his father, a medicine man as well as a descendant of a Sauk chief, died, he left Black Hawk with a noble rank. Black Hawk grew in stature as a war leader while burnishing his reputation against Sauk enemies like the Osage, so that by the time the War of 1812 came around, he was a well-rounded soldier and leader.

When Treaties Weren’t Treaties

During America’s growth as an empire, Native Americans were handicapped by impossible disadvantages. Treaties between the American government and Native Americans were usually written only in English, typically with Native Americans facing overwhelming military superiority. Encroachment by the technologically superior Europeans also created strife among various groups, who turned on each other with increasing frequency over dwindling parcels of land.

Substantial literacy issues meant that Native Americans often signed agreements they didn’t understand, often without a shot being fired.

Black Hawk relays one such story when he describes an attempt by his people to atone for a murder committed by a Sauk. The Sauk culture considered it entirely appropriate to make financial amends to the family who suffered the murder. So the Sauk sent an expedition to St. Louis for negotiations.

The result was an 1804 treaty that moved their village to the west bank of the Mississippi and merged it with another existing Sauk village. This would be the beginning of the Algonquin exodus from the Mississippi.

One of the Sauk representatives, Quashquame, told the story to Blackhawk:

On our arrival at St. Louis … The American chief told us he wanted land. We agreed to give him some on the west side of the Mississippi, likewise more on the Illinois side opposite Jeffreon. When the business was all arranged we expected to have our friend released to come home with us. About the time we were ready to start our brother was let out of the prison. He started and ran a short distance when he was SHOT DEAD!

Native American relations with European invaders were replete with stories like this, along with simple swindles. For example, that same Sauk leader, Quashquame, apparently still wishing to remain east of the river, later helmed a small village east of the Mississippi, but further south of the one he lost in 1804. Quashquame probably thought, “Well, this new village is a hundred miles south of the village I abandoned by treaty. We should be good.”

Nope. It wasn’t good.

In 1824, Captain James White was able to purchase the village from Quashquame for some hooch and two thousand bushels of corn.

Black Hawk Never Acknowledged the Legitimacy of the 1804 Treaty

Black Hawk and a band of like-minded Algonquin from the Sauk and Fox tribes disavowed the legitimacy of the 1804 treaty, declaring that Quashquame had violated an ancient Sauk tradition that relied on consensus, and that his agreements with white settlers were not valid because he made them without consultation.

During the War of 1812, Black Hawk and other Sauk and Fox frequently attacked Fort Madison, a fort near modern-day Keokuk, along with the occasional American settlement along the Mississippi.

He remained hostile towards white settlers attempting to populate the banks of the Mississippi along what is now the Iowa and Illinois border.

Black Hawk’s followers were never happy with the treaty that had forced most of them to the west side of the Mississippi. Presumably, they were not too fond of Quashquame’s later propensity for trading hooch for Algonquin villages, either.

I suspect that somewhere, some Midwestern college professor has written a 500-page tome on the weaponization of alcohol against Midwestern Native American tribes.

Illinois is full of Native American references like “Blackhawk”

We can’t know what was truly in the mind of the Chicago Blackhawks’ first owner, Frederic McLaughlin.

But there are hints.

McLaughlin came up through the ranks of society as an army officer commanding the 333rd Machine Gun Battalion of the 86th Infantry Division during World War I. The division’s nickname was the Blackhawk Division, named after our friend Black Hawk.

If you are a military commander, would you name your division after a person you held in low regard?

But I digress. For the sake of argument, let’s assume McLaughlin had utter contempt for Black Hawk, and the naming of his division was just some weird inside joke.

This still leaves us with the problem of analyzing the proper names of Illinois’ civic infrastructure.

For reasons good or bad, Illinois is full of cities, towns, streets, parks, rivers, and counties named after Native American people and nations.

The name “Illinois” itself is derived from the name given to groups of Native Americans that French Catholic missionaries encountered. Take a look at this screenshot of a map of Park Forest, Illinois:

The Streets and Parks of Park Forest

Park Forest was one of the first planned communities for WW2 vets coming home from the war.

The town was featured in William H. Whyte’s The Organization Man, a best-selling book considered one of the 20th century’s most influential books on management.

Let’s look at the names of some of the village’s streets and parks named after Native American nations and leaders on our map, and what they represent.

Why? Because the obvious question isn’t, “Should the village of Park Forest rename them all?” The question really should be, why don’t we know more about the people behind these names?

Remembering those who were lost to ethnic cleansing isn’t a guilt trip. If you’re a non-Native American, it’s not your fault that this happened. But remembrance is an opportunity to give value to the lives of those who were here before most Americans. So let’s have a look at the village’s nomenclature (in no particular order).

Keokuk Park

Keokuk was a Sauk leader and Black Hawk’s rival. He was his rival partly because he didn’t want to fight the British, realizing that the Sauks were badly outgunned. But he was also his rival because he kept giving in to American demands.

In the modern era, Keokuk would be called an appeaser. He tried to make nice with the American empire and kept moving west as a result. Eventually, he and his people ended up on a reservation in Ottawa, Kansas.

His son continued his father’s sad legacy, and eventually, his dispirited tribe ended up in Oklahoma.

Shabbona

Shabbona, a Potawatomi chief, was another rival to Black Hawk in the sense that he argued against hostilities against white settlers. His reasons appeared to have been strategic. He realized they were badly outgunned, and he was concerned that any war with the American military would be disastrous for his people.

Minocqua

This street name is derived from the Ojibwe word “Ninocqua,” meaning “noon-day rest.” It’s also a town in Wisconsin. Maybe someday a Midwestern college professor will write a 500-page book on why a street in a Chicago South Suburb and a town in Wisconsin both were named after the Ojibwe word for “noon-day rest.”

Iroquois

If you haven’t heard of the Iroquois, you can’t call yourself an American. Just sayin’. If you live elsewhere in the world, then you should know that the Iroquois was a confederacy of a number of Iroquois-speaking nations mostly in the northeast and Great Lakes regions of the United States and southeast Canada.

A midwestern college professor could easily write a thousand-page tome on these folks and probably has. They are also referred to as the Haudenosaunee, as is the confederation of several Native American nations that made up the confederacy. The fate of this confederacy is discussed a bit later in this essay.

Mantua

Although there is a somewhat French word “mantua”, it’s safe to say that since the street Mantua in Park Forest is buried in the middle of a bunch of streets with Native American names, the etymology of Mantua, in this case, is Native American, too. The good folks in Mantua Township, in New Jersey, seem to think the word originates from a Native American word for frog. So let’s just go with that.

Miami

The city of Miami in Florida is spelled incorrectly. It should be Mayaimi, Florida, if it wants to properly represent the Mayaimi people, who were pretty much slaughtered and sold into slavery so that Americans could frolic on Miami Beach.

The Miami people referred to in the street name for Park Forest are from the Great Lakes region. They were Algonquian-speaking people who were not directly related to the Florida First Settlers. They occupied territory in North-central Indiana, southwest Michigan, and western Ohio. By 1846, most of the Miami had been forcefully displaced to Indian Territory (which we now call Kansas — 1.0% Native American), and later Oklahoma.

Nashua

The Nashua were Algonquian people living in what is now known as the Nashua River valley in the northeastern portion of Worcester County, Massachusetts. The name means “river with a pebbled bottom”.

Little known fact: During King Philip’s War, the Nashua sachem (chief), Monoco, kidnapped a Lancaster villager named Mary Rowlandson.

America being America, this led to a bestselling book called A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson and launched a new genre called captivity narratives.

Okay, it wasn’t America yet (it was only 1675), but you can sort of see how Americans became the people they became. Today, she’d probably have a reality TV show called Keeping up with the Rowlandsons.

Ottawa

The Ottawa lived along the Ottawa River in eastern Ontario and western Quebec when the Europeans arrived. The lands they ultimately lost included Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. But they had a city named after them in Canada, so that’s cool.

Onarga

Among the great oak trees twinkled the tiny campfires of the Iroquois. It was the time of the Harvest Moon and the Great Spirit had been kind. Never had there been so good a crop of Indian corn, the herds of buffalo roamed in ever increasing numbers over the great plains, the streams abounded in fish, and the Indians were happy.

At the door of the wigwam sat the great chief of the Iroquois and by his side sat his daughter, Onarga, fairest of the Indian maidens. Together they looked out to where the leaves of corn rustled in the gentle breeze, and then to where the moonlight filtered through the branches of the giant Oaks and danced upon the thick, wavy grass.

“Father,” asked the girl, “why does the North Wind rustle like the waves of many waters through the leaves of the Oaks and across the fields of corn?”

That’s all I got. You can read more here:

https://countryarbors.com/about-us/the-legend-of-princess-onarga

It’s kind of sad thinking about this stuff, isn’t it?

Nokomis

Nokomis was Hiawatha’s grandmother in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, The Song of Hiawatha, which was a distillation of Nanabozho stories. Nanabozho stories were stories told by the storytelling spirit Nanabozho.

Nokomis is an important character in Longfellow’s poem, mentioned in these lines:

By the shores of Gitche Gumee,

By the shining Big-Sea-Water

Stood the wigwam of Nokomis

Daughter of the moon Nokomis.

Dark behind it rose the forest.

If Gitche Gumee sounds familiar, you’re probably my age and are about ready to seek out a Gordon Lightfoot song.

Niagara

Some of the most interesting early American historical stories are derived from the Niagara area of North America. Among the earliest settlers in the Niagara Peninsula were the Onguiaahra people, who arrived from southwestern Ontario between 1300 and 1400 A.D. The name Niagara is derived from these people. It’s sort of awesome thinking that these people were in Ontario in 1300. And before.

Remember when I mentioned the Attawandaron people — or, as the French called them, Neutrals? They were called Neutrals because they tried to act as peacekeepers between the Hurons and Iroquois as those two groups moved into Onguiaahra territory.

One reason that Native American people were so easily removed by American settlers was that some of them had a habit of removing each other, so they were accustomed to losing a war and moving off their land as a result.

In the Niagara area, for example, the Onguiaahra were pushed out by the Hurons and Iroquois. The Attawandaron, trying to get folks to stop fighting, were pushed out by the Iroquois, who also managed to push the Hurons to Michigan.

When the Attawandaron were at their peak, they were led by Jikonsaseh, a queen of sorts. There were as many as 40,000 Attawandaron. They were traders, farmers, and merchants. Then, in 1626, a Frenchman named Etienne Brule came and crashed the party as the first European in the area. The strife created by the French invasion helped instigate a war between the Seneca, who occupied the east bank of the Niagara River near Lake Ontario, and the Hurons. The Hurons retreated from their lands, but a group called the Wenroe moved in with the help of the Attawandaron.

See where I’m going with this? But let’s be clear about what you may have learned in your American history classes, which often teach us that Native Americans were constantly at war with one another over land.

They were at war with one another over land because of European encroachment, which created a domino effect. This is not to suggest that Native Americans never fought each other before Europeans arrived, but it’s fair to say they did so with greater frequency after the European invasion.

The Niagara area is a case in point. European settlement created incredible stress. Ethnic cleansing usually does.

Sauganash

Sauganash was a Potawatomi chief with European ties and bloodlines. He played a key role as a facilitator between whites and Native Americans during the development of Chicago.

He began his diplomatic career as an interpreter for the famous Shawnee leader Tecumseh when the Shawnee and other Ontario First Nations backed the British during the War of 1812.

Sauganash later worked for the British in Canada before moving to Fort Dearborn, which was the precursor to Chicago on Lake Michigan. He acted as a Justice of the Peace and negotiated with the Winnebago (even our RVs are named after the vanquished) to help prevent an uprising in 1827. He also sided with whites against Black Hawk’s efforts on behalf of the Sauk and Fox nations by discouraging Native American bands from joining Black Hawk’s efforts.

Sauk Trail

Named after the Sauk Trail of Illinois, Michigan, and Indiana, this is a major residential thoroughfare in Park Forest.

Sauk Trail is one of many ancient Sauk hunting trails. There is some evidence that it was used to track mastodons, as there was a mastodon trail that ran alongside the Sauk hunting trail. If you see a mastodon walking along the side of Sauk Trail in Park Forest, that might be a sign you ingested peyote before you drove. Not recommended.

Seneca

The Seneca lived just south of Lake Ontario. Today, more than 10,000 Seneca live in the United States.

Today, there are three federally recognized Seneca tribes: two in New York State and one in Oklahoma. The Seneca-Cayuga Nation, in Oklahoma, is descended from yet another group relocated during the years of North American ethnic cleansing.

Before their removal, the Seneca were New Yorkers, living between the Genesee River and Canandaigua Lake. They joined the Iroquois in 1142 AD, according to an oral tradition that reflects a solar eclipse in the year that the Seneca joined the Iroquois.

The Seneca, in what became the Northeast’s most powerful Native American empire, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, became quite dominant. The confederacy remained a powerful force until the Revolutionary War, when it disintegrated over a dispute among the various nations over which side to favor — fueled mostly by the Oneida and Tuscarora, who were persuaded to join the Americans.

Other groups within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy were wildly opposed to any cooperation with Americans, not in small part because of this complaint about King George III written into the American Declaration of Independence:

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

The truth about Haudenosaunee was quite different. Most Haudenosaunee took warfare quite personally, with each death an affront to the Great Spirit. One Seneca who participated in the war, Governor Blacksnake, said of the war, that “it was great sinfull by the sight of God”.

Tragedy engulfed the Haudenosaunee during the Revolutionary War courtesy of the Sullivan Expedition, a retaliatory mission conceived by George Washington after a series of destructive raids by Haudenosaunee warriors in northern Pennsylvania and northern New York settlements on behalf of the British.

The Haudenosaunee attacks climaxed in November 1778. Two companies of Loyalist rangers and more than 300 Iroquois warriors initiated the Cherry Valley Massacre, which killed more than 30 settlers, mostly women and children.

Washington ordered General John Sullivan to mount a retaliatory strike designed to wipe out dozens of Native American villages on a long march from southern Pennsylvania, almost up to the southern shores of Lake Ontario in New York. The retaliation was focused on destruction. Sullivan’s orders were to raze every village in his path, take as many prisoners as possible, and spare no lives based on gender or age.

Washington was determined to launch a campaign of terror, and he did. The Sullivan March broke the back of the Haudenosaunee Confederation. I never read about this genocide in my public education history textbooks. Did you?

Origination of the name for Chicago

Chicago was once sort of the butcher capital of America. It stunk badly, too, especially before the automotive age. There were meat plants all over the place, and horse dung in the streets. I guess that’s why it was named after Native American words representing a pungent smell.

The word “Chicago” originates from the Algonquin word, “shikaakwa,” meaning “striped skunk” or “onion.” The generally accepted theory is that the city was given this name because area rivers and lakes had lots of wild leeks and onions.

The explorer Robert de LaSalle wrote in his September 1687 memoir, “We arrived at the said place called ‘Chicagou’ which, according to what we were able to learn of it, has taken this name because of the quantity of garlic which grows in the forests in this region.”

Take that with a grain of salt. The reason the name stuck was probably that it was one of the stinkiest cities on the continent.

Many Illinois Cities and places are named with Native Americans in mind

Cities and villages with Native American-based names outside of Chicago include Annawan, Algonquin, Ashkum, Blue Mound, Cahokia, Calumet Park, Channahon, Chebanse, Detroit, DuBois, DuQuoin, Kaskaskia, Kankakee, Kewanee, Lake Ka-Ho, Loami, Mackinaw, Mahomet, Makanda, Manhattan, Menomonie, Minooka, Moweaqua, Muncie, Neponset, Niantic, Oconee, Okawville, Shawneetown, Onarga, Oquawka, Owaneco, Paw Paw, Pawnee, Pecatonica, Peoria, Pesotum, Pocahontas, Pontoosuc, Potomac, Raritan, Roanoke, Sauget, Sauk Village, Seneca, Shabbona, Tamaroa, Tiskilwa, Toledo, Tolono, Tonica, Towanda, Wenorah, Waukegan, and Wyanet.

There are rivers: The Illinois, Mississippi, Ohio, Wabash, Kankakee, Kaskaskia, Chicago, West Okaw, Sangamon, Mackinaw, Kishwaukee, Pecatonica, Sinsinawa, Menominee, Waukegan, and Calumet.

And there are lakes: Lake Michigan, Nippersink Lake, Pistakee Lake, Saganashkee Slough.

There are city parks, state parks, regional parks, counties, and courthouses.

The whole state is a celebration of Native America. You’d think that Illinois would have a huge Native American population.

Native Americans make up 0.3% of the population of Illinois.

Most of them were forcibly removed through ethnic cleansing. However, I would not be in favor of changing all these names, because that would give credibility and permanence to the ethnic cleansing that helped expand the American continental empire. It would help remove the First Settlers from American history.

Similarly, the name Blackhawks is a celebration of a brave rebel who actively fought against ethnic cleansing.

Illinois is not alone in “celebrating” Native American names

Illinois, of course, is not the only U.S. state that leans heavily on Native American tradition for its naming conventions.

From the Florida State Seminoles to the state of Delaware on the East Coast, Native American references abound.

It’s unlikely we will ever reach a consensus that results in renaming all the cities, towns, and streets we have named after Native American nations and their leaders. And, to repeat, it doesn’t seem like we should, either.

What we can do, instead, is celebrate these nations and their people. Americans can continue to seek ways to atone for our sins against them, too.

Something tells me we can do better than offering them carte blanche on casinos.

What might a national reconciliation effort look like? We often hear about reparations for Black Americans, who also suffered at the hands of the American Empire. That is another, very valid topic. What might a reparation effort towards Native Americans look like?

That’s a story for another day.

Notes

Sources for this essay include:

¹ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Hawk_(Sauk_leader)

² https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sauk_people#History

³ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Hawk_(Sauk_leader)#Early_life

⁴ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fox_Wars

⁵ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quashquame#Villages

⁶ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_Blackhawks#cite_note-McLaughlin_Years-6

⁷ https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=KE008

⁸ https://www.legendsofamerica.com/tribe-summary-n/2/#Neutrals

⁹ http://www.nativetech.org/Nipmuc/placenames/mainmass.html

¹⁰ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seneca_people#Involvement_in_the_American_Revolution

¹¹ https://archive.org/details/peopleshistoryof00raph

¹² https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sauk_Trail

¹⁴ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Park_Forest,_Illinois

I didn’t do my usual footnote format here because, well, I forgot, so I just plunked the list of resources I used to research this with.

Disclaimer: I am most definitely not an expert on Native American culture, although I’m fascinated enough by it to understand that the politics of North American First Nations and Settlers was incredibly complex, even before the arrival of Europeans. If you are an expert and you find an inaccuracy, include it in the comments, and I’ll make an edit! Thanks for reading.

Pedofuhrer 😂 I support this name change.

Excellent essay, Charles.

Excellent work, Charles! Very informative.