CoreCivic’s Ethnic Cleansing Program

The stories of children suffering at the hands of ICE in a CoreCivic concentration camp in Dilley, Texas, and overwhelmed first responders in rural Georgia

“The Children of Dilley,” ProPublica’s chilling new story about children captured by the regime’s ethnic cleansing program, and a story from The Intercept about an overwhelmed rural first response system, have one thing in common: CoreCivic, the regime’s private concentration camp contractor.

Fourteen-year-old Ariana Velasquez had been held at the immigrant detention center in Dilley, Texas, with her mother for some 45 days when I managed to get inside to meet her. The staff brought everyone in the visiting room a boxed lunch from the cafeteria: a cup of yellowish stew and a hamburger patty in a plain bun. Ariana’s long black curls hung loosely around her face and she was wearing a government-issued gray sweatsuit. At first, she sat looking blankly down at the table. She poked at her food with a plastic fork and let her mother do most of the talking.

She perked up when I asked about home: Hicksville, New York. She and her mother had moved there from Honduras when she was 7. Her mother, Stephanie Valladares, had applied for asylum, married a neighbor from back home who was already living in the U.S., and had two more kids. Ariana took care of them after school. She was a freshman at Hicksville High, and being detained at the Dilley Immigration Processing Center meant that she was falling behind in her classes. She told me how much she missed her favorite sign language teacher, but most of all she missed her siblings.

I had previously met them in Hicksville: Gianna, a toddler who everyone calls Gigi, and Jacob, a kindergartener with wide brown eyes. I told Ariana that they missed her too. Jacob had shown me a security camera that their mom had installed in the kitchen so she could peek in on them from her job, sometimes saying “Hello” through the speaker. I told Ariana that Jacob tried talking to the camera, hoping his mom would answer.

Stephanie burst into tears. So did Ariana. After my visit, Ariana wrote me a letter.

“My younger siblings haven’t been able to see their mom in more than a month,” she wrote. “They are very young and you need both of your parents when you are growing up.” Then, referring to Dilley, she added, “Since I got to this Center all you will feel is sadness and mostly depression.”

So begins the story from ProPublica describing their reporters’ visits to a concentration camp in Dilley, Texas, “nearly 2,000 miles away from Ariana’s home,” according to the article.

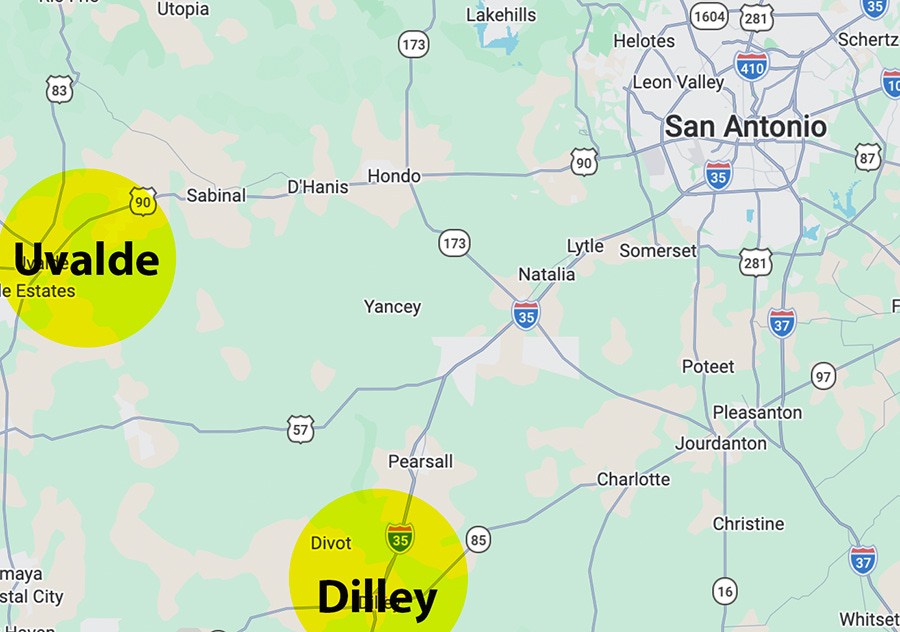

This part of Texas has not been friendly to children over the last several years.

Once again, an infographic says a thousand words:

To be fair, Dilley is not one of Obama’s finer moments. The camp was opened during the Obama administration to hold families detained at the border.

Those few of us who have been arguing all these years against immigration crackdowns not accompanied by massive investments in administrative judges who can process the victims have been warning about this kind of inevitability for as long as the places have been open.

Even if a facility like this is opened with the rare noble intention, the very nature of the for-profit prison system is to grow the business and strip its denizens of all but the most basic necessities to keep enough of them breathing that nobody notices the obscene attrition rate.

Private prison companies have never been a good idea. They’re especially wicked when they are used to build, expand, and administer concentration camps that hold children captive far away from their homes.

Let’s let the children speak more to this. From the ProPublica article comes this from a 14 year old Columbian girl, who:

wrote a letter about how the guards at Dilley “have bad manner of speaking to residents.” She wrote, “The workers treat the residents unhumanly, verbally and I don’t want to imging how they would act if they where unsupervised.”

One nine-year-old girl, Maria Antonia Guerra, from Colombia:

drew a portrait of herself and her mother wearing their detainee ID badges. A note on the side said, “I am not happy, please get me out of here.”

Out of 3,500 people being held in the CoreCivic prison camp in Dilley, ProPublica points out, about half of them are minors.

Let that sink in for a minute.

This is what happens when you see those street scenes from Minneapolis:

After the chemical weapons are thrown, after American citizens are shot, after innocent people are pulled out of their cars by cosplaying ICE Jan Sixers wearing Special Ops uniforms, kids get rounded up and thrown into a concentration camp thousands of miles away from the snow and ice of Minneapolis.

The regime wants to build more of these. A lot more. So that more stories like this from ProPublica are told:

There were children in Dilley who were so distraught they cut themselves or talked about suicide, several mothers told me. Recently, two cases of measles were discovered in the center.

Moms told me that their kids had lost their appetites after finding worms and mold on their food, had trouble sleeping on the facility’s hard metal bunk beds in rooms shared by at least a dozen other people, and were constantly sick.

“The shock for my daughter was devastating,” Maria Alejandra Montoya from Colombia wrote in an email to me about her daughter Maria Antonia. “Watching her adapt is like watching her wings being clipped. Hearing other children fight over card games at the tables makes me feel like we are not mothers and children, but inmates.”

We now live under a regime where a school desk looks like this:

Instead of this:

A Texas non-profit, RAICES (Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services), has “raised concerns about insufficient medical care on at least 700 occasions since August 2025,” according to ProPublica:

Kheilin Valero from Venezuela, who was being held with her 18-month-old, Amalia Arrieta, said shortly after they were detained following an ICE appointment on Dec. 11 in El Paso, Texas, the baby fell ill. For two weeks, she said, medical staff gave her ibuprofen and eventually antibiotics, but Amalia’s breathing worsened to the point that she was hospitalized in San Antonio for 10 days. She was diagnosed with COVID-19 and RSV. “Because she went so many days without treatment, and because it’s so cold here, she developed pneumonia and bronchitis,” Kheilin said. “She was malnourished, too, because she was vomiting everything.”

Gustavo Santiago, the 13-year-old boy who’d been living in Texas, said he has been sick several times since he and his mom were detained on Oct. 5 of last year at a Border Patrol checkpoint. His mom, Christian Hinojosa, said that when Gustavo had a fever, the medical staff told her he was old enough for his body to fight it off without medication, so she sat up with him all night, draping him in cold compresses.

Among logs we obtained of calls made to 911 and law enforcement about the facility since it began accepting families again last spring, I found pleas for help for toddlers having trouble breathing, a pregnant woman who passed out and an elementary-school-aged girl having seizures. Local authorities were also called in for three cases of alleged sexual assault between detainees.

Did someone say 911?

Yes. Yes, they did. The Intercept, too, has found some interesting stuff in rural Georgia. The Intercept describes the current situation at Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, which is also run by CoreCivic:

“Male detainee needs to go out due to head trauma,” an employee at a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s detention center in Georgia tells a 911 operator.

The operator tells the employee at Stewart Detention Center that there are no ambulances available.

“It’s already out — on the last patient y’all called us with,” the operator says.

This quote is pulled from an Intercept story about an overwhelmed rural Georgia first response system.

I’ll add some more from the Intercept story:

The call was one of dozens from the ICE detention facility seeking help with medical emergencies during the first 10 months of the second Trump administration, a sustained period of high call volume from the jail not seen since 2018.

Emergency calls were made to 911 at least 15 times a month from Stewart Detention Center for six months in a row as of November 1.

Like the call concerning a detainee’s head trauma from April 1, emergency dispatch records show that the ambulance service in Stewart County, Georgia, where the detention center is located, has had to seek help outside the county more than any time in at least five years — including three instances in November alone.

The burden on rural Stewart County’s health care system is “unsustainable,” said Dr. Amy Zeidan, a professor of emergency medicine at Atlanta’s Emory University who researches health care in immigration detention.

Emory University is the home of the folks who fixed my broken brain. I trust them. They know of what they speak when it comes to healthcare.

The strategy of the regime and CoreCivic, the regime’s privateers, is simple: Drop the concentration camps into rural areas, where resistance is not as high as it would be in an urban area.

Even if this were an acceptable policy, nobody considers the side effects. Rural areas are already burdened with slow response times from emergency response personnel.

Rural communities that allow CoreCivic to build concentration camps soon discover that when Uncle Hugh strokes out after raging at Bad Bunny, there’s nobody to save him the way I got saved by Emory. That’s because the ambulance service is probably responding to a problem at the CoreCivic facility. Poor Uncle Hugh dies with a clenched fist as Bad Bunny sings about love and weddings.

It’s easy to say, “Dumb shits,” but the problem extends to the original victims, who are often American citizens rounded up by ICE cosplayers for the crime of being brown. A head injury goes untreated. A shiv attack leaves someone to bleed out. A virus wipes out a cell block.

More from the Intercept:

911 calls from Stewart included several for “head trauma,” such as one case where an inmate was “beating his head against the wall” and another following a fight.

Impacts of the situation are hard to measure in the absence of comprehensive, detailed data, but they extend both to Stewart’s detainee population — which has increased from about 1,500 to about 1,900 during the Trump administration — and to the surrounding, rural county. (ICE did not respond to a request for comment.)

Data obtained by The Intercept through open records requests shows that the top four reasons for 911 calls since the onset of the second Trump administration have been chest pains and seizures, with the same number of calls, followed by stomach pains and head injuries.

It’s easy for us to say, sitting on our cozy chairs, that, hey, maybe all those head injuries come from fights, and maybe the captives should stop fighting amongst themselves, but there are significantly more studies on this planet showing a direct correlation to overcrowding and violence than there are compassionate human beings in the Republican Party or Team Predator.

CoreCivic will be a huge beneficiary of the ICE funding now on the table during yet another Republican government shutdown debate.

Per Seeking Alpha:1

CEO Damon T. Hininger announced substantial progress on contracting several idle facilities, stating, “Since our last earnings call, we announced new awards at the 600-bed West Tennessee Detention Facility, the 2,560-bed California City Immigration Processing Center, the 1,033-bed Midwest Regional Reception Center and the 2,160-bed Diamondback Correctional Facility. In aggregate, these 4 new contract awards are expected to generate annual revenue of approximately $320 million once we reach stabilized occupancy.”

Hininger added that these new awards set up CoreCivic for a stronger 2026, noting expectations of “annual run rate revenue to be approximately $2.5 billion and annual run rate EBITDA to increase by $100 million to over $450 million.”

President & COO Patrick Swindle highlighted that federal partners comprised 55% of total revenue in Q3, with ICE revenue up $76.2 million or 54.6%…

…Management reiterated its confidence in reaching a $2.5 billion revenue run rate and over $450 million in EBITDA once new facilities are fully ramped, despite near-term margin pressures from start-up costs.

They’re making a killing, but in all the wrong ways.

Or fund me one time…

And hey, even restacking helps fund me indirectly…

Sources

ProPublica: https://www.propublica.org/article/life-inside-ice-dilley-children

The Intercept: https://theintercept.com/2025/12/12/stewart-911-calls-ice-ambulance-emergency/

Footnotes

SA. 2025. “CoreCivic Outlines $2.5B Revenue and $450M EBITDA Run Rate for 2026 as New Contracts Ramp Up.” Seeking Alpha. November 7, 2025. https://seekingalpha.com/news/4518362-corecivic-outlines-2_5b-revenue-and-450m-ebitda-run-rate-for-2026-as-new-contracts-ramp-up.