Should Chicago Be Renamed Potawatomi?

The Potawatomi have finally been given a strip of land in Illinois, but shouldn't there be more?

Our country was given to us by the Great Spirit, who gave it to us to hunt upon, to make our cornfields upon, to live upon, and to make down our beds upon when we die. And he would never forgive us, should we bargain it away.

— Potawatomi Chief Metea

These days, Native American nations in the American Midwest have generally been reduced to a form of hunting that their ancestors could never have imagined. Instead of hunting for buffalo or other game, they hunt for parcels of land upon which they hope to open casinos.

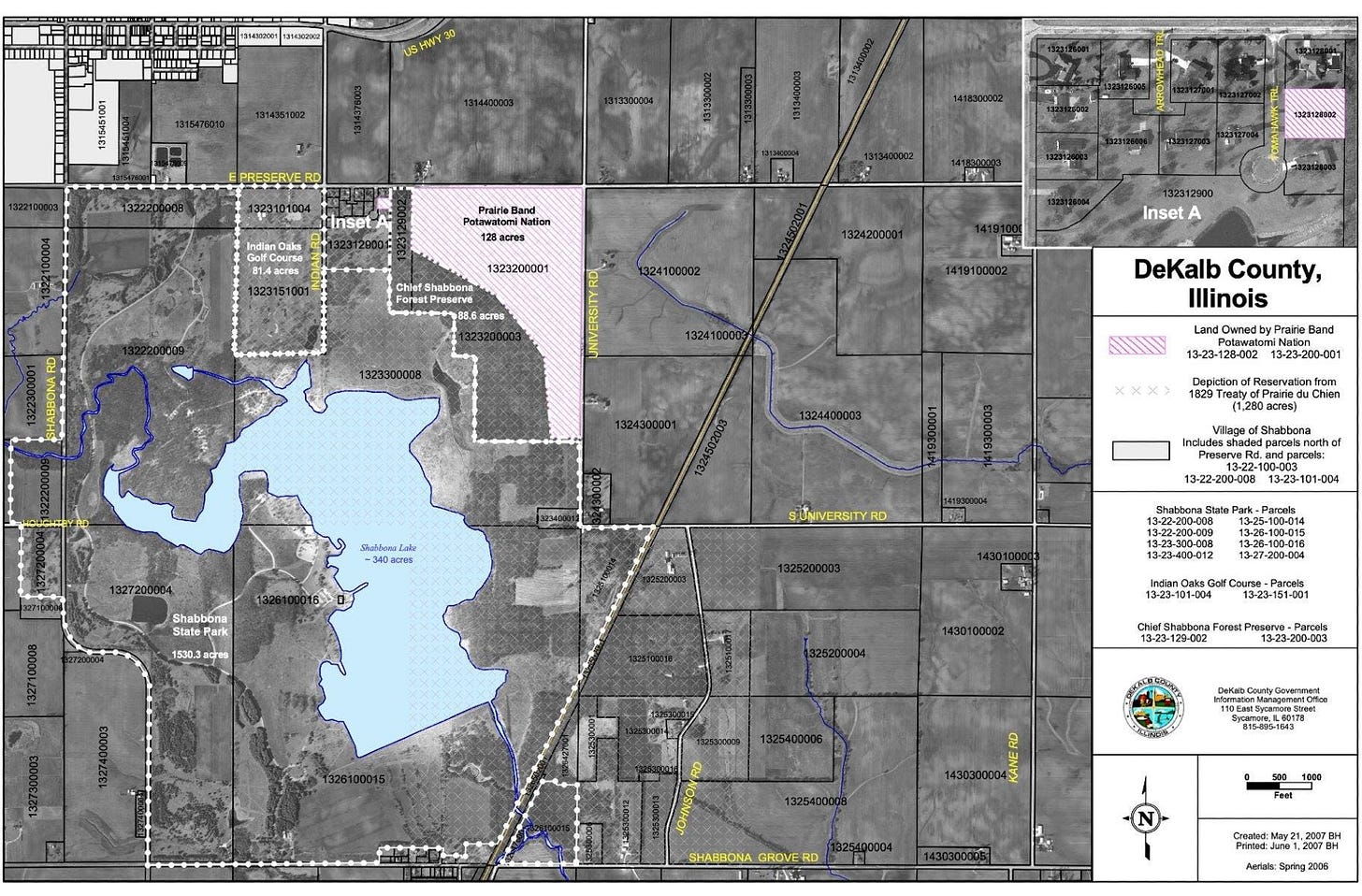

This happened recently in Shabbona, Illinois, a small plot of land in DeKalb County, Illinois. DeKalb County is known locally mostly as the home of Northern Illinois University, the birthplace of model Cindy Crawford1, and some of the best dadgum sweet corn you’ll ever taste.

The sweet corn tastes like candy, and when you slather it with butter, it will startle your senses to the point that you’ll swear off the cardboard the rest of the country outside of the Midwest tries to call sweet corn.

The small tract of land was awarded to the remnants of a once powerful Native American nation called the Potawatomi, an amalgamation of several tribes that banded together during a century or two of conflict harassment with by the United States and Britain.

Technically, the Potawatomi are the beneficiaries of a land transfer made through a trusteeship held by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs through the auspices of a landmark 2020 Supreme Court ruling, McGirt v. Oklahoma2, which grants sovereignty to Native American tribal nations over land that tribal nations can prove were intended as reservation land but were for some reason wrested away from them.

Once such a land transfer is made, the Native American nations can do what they want with the land as if it were part of a sovereign nation. In essence, then, tiny Shabbona is now part of an independent nation governed by the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, based in Kansas.

The net effect is that college kids at the 25,000-student Northern Illinois University in nearby DeKalb could soon be a short drive from a casino.3 Luckily, NIU is best known for, aside from one of the the unlikeliest wins in college football history against Notre Dame this year, its accounting school. So the students should be able to easily track their losses.

Each effort by Native Americans to gain any payback for their years of tears is always opposed by some group or another. Shabbona has been no exception. The sovereignty of this small piece of land was fought with vigor by locals who objected to the possibility of a casino the tribal nation had proposed after the Potawatomi bought about 180 acres of the land in 2004.

In raising its objections on its website4, the organization opposing the land transfer, DeKalb County Taxpayers Against the Casino (DCTAC), quotes one of America’s most renowned Christo-nationalist lobby groups, Focus on the Family:

“Gambling is a vice industry built on deception and fed by the intentional exploitation of human weakness for the sole purpose of monetary gain.”

This is probably true. But Native American groups rightly believe that if the descendants of the people who stole their land want to fritter away their money at blackjack tables, they should be able to do so. That tribal nations might take delight in watching their ancestral tormenters ruin their finances seems like a fair yin/yang fight for balance to me.

Besides. You can be sure that the “focus on the family” will disappear the minute the casino is built and its massive parking lot is full.

The Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation has been trying to regain sovereignty over the 180-acre parcel of land next to Shabbona Lake State Park since long before they owned it. But owning land isn’t anywhere near as advantageous as being able to do whatever you want with it, because land is always subject to local, state, and national regulations no matter who owns it.

This is not the case when the land is granted sovereignty to an Indian tribal nation. When that happens, the tribal nation writes the laws covering land use.

The Potawatomi proposed their casino on the property (see the image below) in 2007 but were rejected by the National Indian Gaming Commission because of the land’s uncertain status5. This status is now resolved.

The Potawatomi, like hundreds of other tribal nations you’ve never heard of, were originally kicked off their land as part of America’s relentless series of ethnic cleansing pogroms.6 The most famous of these was the Indian Removal Act7 signed by Andrew Jackson in 1830, which codified the process into formal law.

The Indian Removal Act relied on individual “treaties” like the Treaty of New Echota, a treaty between the U.S. government and a few hundred Cherokee Indians who, the government claimed, represented the tens of thousands of Cherokee living in Georgia at the time.

The act was advertised as a way of offering land to Native Americans in return for relocating to lands west of the Mississippi. But there was no choice involved. The offer was this: accept it, or die, which is precisely what happened when Georgia Cherokees, including their Principal Chief John Ross, who wasn’t involved in the treaty “negotiations,” refused the offer.

U.S. President Martin Van Duren recruited General Winfield Scott to enforce the finagled treaty. Scott built six internment camps to incarcerate Native American men, women, and children while the government rounded up as many Cherokee as it could get its hands on.

As many as 50,000 Cherokee from Georgia and Tennessee were force-marched 1200 miles to their destinations, mostly in Oklahoma. It’s been estimated that, during the march, up to 25% of them died from a variety of ailments, from dysentery to starvation to exhaustion.

This event, known as The Trail of Tears,8 was not a one-off event, only the most famous. Native Americans in the Eastern United States lost 25 million acres of land to the process.

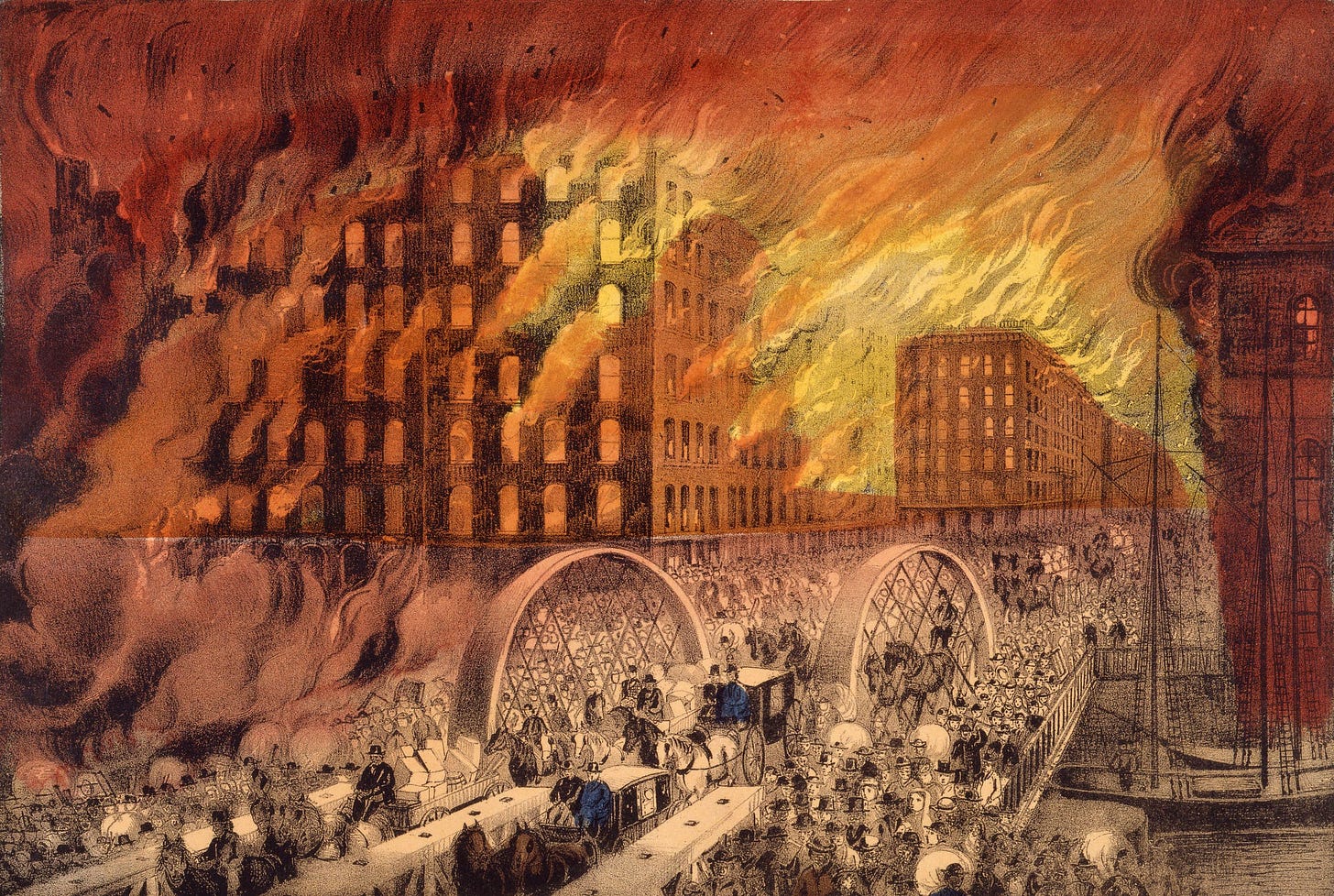

Similarly, the Chicago area, too, saw the bulk of its indigenous population removed.

The first major removal occurred in 1821, nine years before the Indian Removal Act (which, remember, was just a codification of existing policy into law) through the 1821 Treaty of Chicago.9

When Potawatomi Chief Metea10 was forced to sign the Treaty of Chicago, he gave a heartfelt, earnest speech:11

My Father, — We have listened to what you have said. We shall now retire to our camps and consult upon it. You will hear nothing more from us at present…

Our country was given to us by the Great Spirit, who gave it to us to hunt upon, to make our cornfields upon, to live upon, and to make down our beds upon when we die. And he would never forgive us, should we bargain it away…

…The Great Spirit, who has provided it for our use, allows us to keep it, to bring up our young men and support our families. We should incur his anger, if we bartered it away.

If we had more land, you should get more; but our land has been wasting away ever since the white people became our neighbors, and we have now hardly enough left to cover the bones of our tribe. You are in the midst of your red children. What is due to us in money, we wish, and will receive at this place; and we want nothing more. We all shake hands with you. Behold our warriors, our women, and children. Take pity on us and on our words.

By 1833, when the second Treaty of Chicago was consummated, most Native Americans had received the message: When you are asked to sign a treaty to leave your lands, do so, and then get out, quick, or someone like General Scott will round you up into internment camps and send you far, far away.

The second treaty ceded Lake Michigan’s shoreline to the U.S. government, along with all the rest of the land west of Lake Michigan up to the Mississippi, and north to Lake Winnebago in Wisconsin.

But under a strange quirk of circumstances that has not been well-detailed by history, the stubborn Potawatomi retained a slice of land near tiny Shabbona, where a small reservation was created within the mess of treaties that exiled most Midwestern First Settlers.

Unfortunately for the Potawatomi, when their chief, Shab-eh-nay, returned from a trip to Kansas to visit his displaced family, he discovered that government officials snuck in while he was gone and auctioned off the 1,280-acre reservation. This launched a nearly two-hundred-year battle for the land. The Potawatomi never gave up their claim.

No matter where you live in America, it’s likely you are reading this while sitting on land once occupied by a nation that had managed the land for centuries before your ancestors arrived. In the Midwest, the ownership of these lands looked something like this:

The third largest city in America, Chicago, is no exception.

In 1914, ten years before Native Americans were declared American citizens, the Pokagon Indians made a formal claim on some of Chicago’s prime real estate that today includes the Gold Coast, Lake Shore Drive, and the wealthy hipster enclave of Lincoln Park.

The Pokagon (Pokégnêk Bodéwadmik), a part of the Potawatomi nation that won the Shabbona parcel but is now a separate sovereign nation, tried a little trick to sue the city of Chicago in 1914 to claim ownership of Chicago’s Lake Michigan shoreline.

Some background is necessary here: The U.S. Supreme Court had previously consistently turned back efforts by Native Americans to lay claim to their former lands by, in essence, saying, “Hey, you left. Shouldn’t have signed those treaties that were forced upon you at gunpoint, dummies.”

This “abandonment” principle holds today. It says that since Native Americans left their lands, the lands now belong to the United States.

So the Pokagon tried to claim that they couldn’t have left a strip of land along Lake Michigan that didn’t exist. They argued that the strip of land they wanted was a landfill created shortly after the Chicago Fire to lay down and reuse detritus from the fire’s remains. The landfill, they argued, was placed on a part of their land not covered by the treaty, because it didn’t exist at the time.

That’s a desperate legal argument, but what’s a lost tribe to do?

Hidden in the Supreme Court’s rejection12 of their claim was a fascinating acknowledgment when the court described the Pokagons’ argument:

The Pottawatomie Indians were the owners and in possession as a sovereign nation, as their country, of large tracts of land around and along the shores of Lake Michigan, south of a line running from Milwaukee river, Wisconsin, to Grand river, Michigan, and extending “east and west of said two points and including all of Lake Michigan which is south of said line” — a stretch of a hundred miles.

The court goes on to disavow this claim:

The only possible immemorial right which the Pottawatomie Nation had in the country claimed as their own in 1795 was that of occupancy. Johnson v. M’Intosh, 8 Wheat. 543. If, in any view, it ever held possession of the property here in question, we know historically that this was abandoned long ago, and that for more than a half century it has not even pretended to occupy either the shores or waters of Lake Michigan within the confines of Illinois.

In other words, as I said earlier: “You left, and it’s ours now.” The “abandonment” principle in full view.

This was the Supreme Court of the United States, the nation that took the lands, speaking out on this topic, not the Supreme Court of the Pokégnêk Bodéwadmik, the nation that had lost them, so there’s an obvious conflict of interest.

The Supreme Court then reminded the Pokégnêk Bodéwadmik of the Treaty of Greenville, another “treaty” that stripped land away from Native Americans, this time from Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, and Indiana:

By the Treaty of Greenville, the United States stipulated with the Pottawatomies and other Indians that generally, in respect of a large territory westward of a line passing through Ohio…

…We think it entirely clear that this treaty did not convey a fee simple title to the Indians; that, under it, no tribe could claim more than the right of continued occupancy; that under this was abandoned all legal right or interest which both tribe and its members had in the territory came to an end.

This kind of ruling is why you are sitting in front of a 70-inch television monitor watching bad comedies about Pop-Tarts® instead of benefitting from a nice matriarchal, egalitarian society that worships the earth.

These rulings will never be overturned, of course. They are set in stone harder than the concrete we’ve paved over Native American soil.

But maybe we can each find a way to show a little appreciation for the original ancestors of the land we live in. We can start by understanding that Chicago should, in all fairness, be Potawatomi land. And that every city in America has binding ties to an Indian nation.

Check out the local history of your city. Remember that, from a moral and ethical standpoint, it belongs to a group of people who were forced to leave by a rapacious empire. Seek out their name. Learn about the humble nation that lived in your city two hundred years ago.

Bug-eyed right-wingers will call that last paragraph “woke”.

I call it history. Same thing.

Thanks for reading!

Notes

I despise the word ethnic cleansing because it sounds like a good thing almost to “cleanse” a nation of certain ethnicities. But it’s the common phrase for removing populations, so I stuck with it.

Further reading

The 1833 Treaty of Chicago forced Native Americans off their land, but legal disputes continued for…

In June 1905, the Tribune recalled that some 70 years earlier, diplomacy had been a thriving industry on Lake

Footnotes

Contributors. 2003. “American Model.” Wikipedia.org. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. July 11, 2003. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cindy_Crawford#Early_life.

Torres, Gerald. 2020. “McGirt v. Oklahoma.” Oyez.org. - Oral Argument 2.0 - U.S. Supreme Court Oral Argument Follow-Up Analysis. May 11, 2020. https://argument2.oyez.org/2020/mcgirt-v-oklahoma/.

Recent comments by tribal chairman Joseph “Zeke” Rupnick before the Illinois state legislature contradict this:

The Prairie Band Potawatomi currently operate a hotel and casino complex on their reservation just north of Topeka, Kansas. But tribal chairman Joseph “Zeke” Rupnick assured the House committee the tribe has no such plans for the property in Illinois.

“That has not been our intention,” Rupnick said. “Thirty years ago, when there was no gaming in Illinois, we definitely pushed in that direction. Today, we're just trying to make sure that we get the land secure.”

“Bill That Would Expand Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation’s Reservation Advances in Illinois House.” 2019. WTTW News. https://doi.org/1002587/c2n_sitewide_leaderboard.

“DCTAC - DeKalb County Taxpayers against the Casino.” 2025. Dctac.org. 2025. http://dctac.org/.

A legal analysis regarding the proposed gaming by the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation in DeKalb County, Illinois, focusing on the legal status of the Tribal Parcel and the requirements under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act

PDF: https://dekalbcounty.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/pbpn-sao100107.pdf

Yes, “pogroms” as opposed to “programs.” The use of the word “pogrom” as defined by the Cambridge Dictionary is substantially more meaningful than “program:”

An act of organized cruel behaviour or killing that is done to a large group of people because of their race or religion.

Cambridge Dictionary. 2025. “Pogrom.” @CambridgeWords. 2025. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/pogrom.

“Research Guides: Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History: Introduction.” 2019. Loc.gov. 2019. https://guides.loc.gov/indian-removal-act.

“President Andrew Jackson’s Message to Congress ‘on Indian Removal’ (1830).” 2021. National Archives. June 25, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/jacksons-message-to-congress-on-indian-removal.

Contributors. 2005. “1821 Treaty between the United States and Representatives of the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi Peoples.” Wikipedia.org. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. January 18, 2005. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Chicago

Contributors. 2006. “Chief of the Potawatomi.” Wikipedia.org. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. July 31, 2006. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metea.

Contributors. 2005. “1821 Treaty between the United States and Representatives of the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi Peoples.” Wikipedia.org. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. January 18, 2005. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Chicago.

“Williams v. Chicago, 242 U.S. 434 (1917).” 2025. Justia Law. 2025. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/242/434/.

"Check out the local history of your city. Remember that, from a moral and ethical standpoint, it belongs to a group of people who were forced to leave by a rapacious empire. Seek out their name. Learn about the humble nation that lived in your city two hundred years ago."

Another great column, Charles. Insightful, well researched, and sad...We've done a lot of horrible things in this country. 🙄

This was incredibly powerful and I affirm your work to shine a light on the real history of place here in America. Thank you for this offering—your effort made an impact upon me.