The Story of the Ladybug and the Cockroach

How Instagram and other vanity apps are eating American Culture

The other day I noticed a cute little ladybug attached to my sleeve while enjoying an iced tea at the kitchen table after pruning the tomatoes. My usual response to an insect upon my person is swift assassination. But it was a ladybug. You don’t kill ladybugs.

I was going to walk it outside but it fell to the ground. When any other insect lands on the ground near my feet at home, my first instinct is to squash it into an anthropoid pancake. I don’t want the gnarly little buggers crawling around my rug, waiting for that moment to strike me in my sleep and turn me into a science fiction movie.

But. It was a ladybug. So I gently coaxed it off the carpet with my finger onto a napkin, walked through the living room to the front door, and launched it outside. They’re tough little ladies. I knew “she’d” be okay. It wasn’t quite as satisfying as letting a raptor take to the skies from a gloved hand, but it was good enough.

Then I pondered one of the great mysteries of life. Why do I want to protect ladybugs but commit genocide against other six-legged creatures?

This may seem like a silly question, but it’s related to a serious problem: We’re undergoing an insect apocalypse, which is one of the side effects of climate change that nearly 40% of Americans don’t want to talk about.

Someone like me, who is not a fan of anything that has more than five legs and is small enough to crawl into my boxers, should be cheering for the insect apocalypse. Right? I’ve been known to spend hours chasing one fly around the house because of its incessant buzzing.

But no, this is a real problem for the ecosphere. So I’ve learned to be more tolerant toward the little hounds of hell. Oh, sorry! See? I almost can’t help myself.

My next thought when I pondered the newly freed ladybug was that we tend to take the same attitude toward humans as we take toward the insect world. When we see a disheveled homeless person on the street, often our reaction is negative, even if we feel sorry for them.

But what makes this man a cockroach instead of a ladybug? Is it his bedraggled look? Or is it the sign?

Put him in a suit, shave his beard, cut his hair, maybe even slick it back, and what do you have? A man in a suit with a sign that says, “Seeking human kindness.” The most generous among us will find it amusing. Others will think he’s trying to get attention.

Change the sign to “Will work for food,” and we’ll all think he’s mocking the poor or playing an advanced version of truth or dare, but we’ll still probably admire him for something, even if we don’t know what it is. Because he’s wearing a nice suit.

Conclusion: It’s not the sign.

Appearance means everything in our society. It’s why it took America forever to accept people with physical disabilities into their personal space.

Back in the day when horse poo was so bad that you couldn’t get out of your house without wading through rivers of horse dung, countless people were walking around without a leg or arm because of nasty streetcar accidents. That effectively ended their livelihoods, and they often became street people.

It didn’t matter how well they dressed or if they were well groomed (they usually weren’t because they were at the end of their road). They were missing an appendage, so they became pariahs.

Franklin D. Roosevelt hid his wheelchair from cameras because his handlers correctly thought that Americans would reject him if photos or video reels showing him in a wheelchair were widely circulated. So for twelve years, Roosevelt’s disability, which was triggered by a bout with polio, was hidden from public view.

According to NPR and AP:

Roosevelt contracted polio in 1921 at age 39 and was unable to walk without leg braces or assistance. During his four terms as president, Roosevelt often used a wheelchair in private, but not for public appearances. News photographers cooperated in concealing Roosevelt’s disability, and those who did not found their camera views blocked by Secret Service agents, according to the FDR Presidential Museum and Library’s website.

It wasn’t until 2010 that an intrepid college professor found an old video of Roosevelt in a wheelchair. The video is a great contrast between his physical realities and what his handlers wanted the public to see:

These days, somehow, things have gotten worse. Teenagers are bullied online if they aren’t set at exactly the right weight. It’s easy to blame other teenagers, but our culture is guided by the media. You can’t use the phrase, “fat people,” but you can still refuse to hire them and nobody will raise an alarm.

Social media sites and apps like Instagram and TikTok actively encourage bullying, despite their incessant denials. They don’t encourage it by cheering it on. It’s much more nefarious than that. They encourage it with algorithms.

It’s a set of algorithms that separate humans into ladybugs and cockroaches.

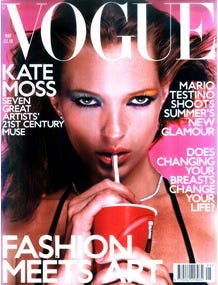

The precedent for this was a print media sphere that pushed women into eating disorders by demanding stick-thin waistlines and precise bust measurements.

And although the Kardashians have gifted us with some minor changes about what is acceptable regarding hip size, the same trend continues.

It’s almost as if the American woman has visited the local tailor, and he’s expanded his tape measure just a tad, then slapped her on the ass and admonished her to keep the rest of her body in line. “You’ve been warned,” he snarls, his long tape measure in his mouth, his fingers poised on his phone to deliver his social death sentence on Instagram.

American women are asked to blow their lips up with Botox or starve themselves to death in order to appeal to, not just men, but now, social media fans. A few extra pounds around your midriff or a face with the slightest puff can lead to a social media apocalypse.

Sadly, celebrities continue to feed the Instagram monster with increasingly seductive professional photography, usually accompanied by some crafty Photoshop work. They’re not helping.

This march of celebrities continues from one generation to the next, like a horde of scalpel-wielding butchers demanding that their young cohorts slice a wedge of fat from their waistlines if they want to remain viable participants in a merciless contest that is the psychological equivalent of a Squid Game.

So the next time you post an Instagram photo and feel a little less than, ask yourself who the real cockroach is in this equation. Cuz it ain’t you.