The Trial Of Summary James - Chapters One and Two

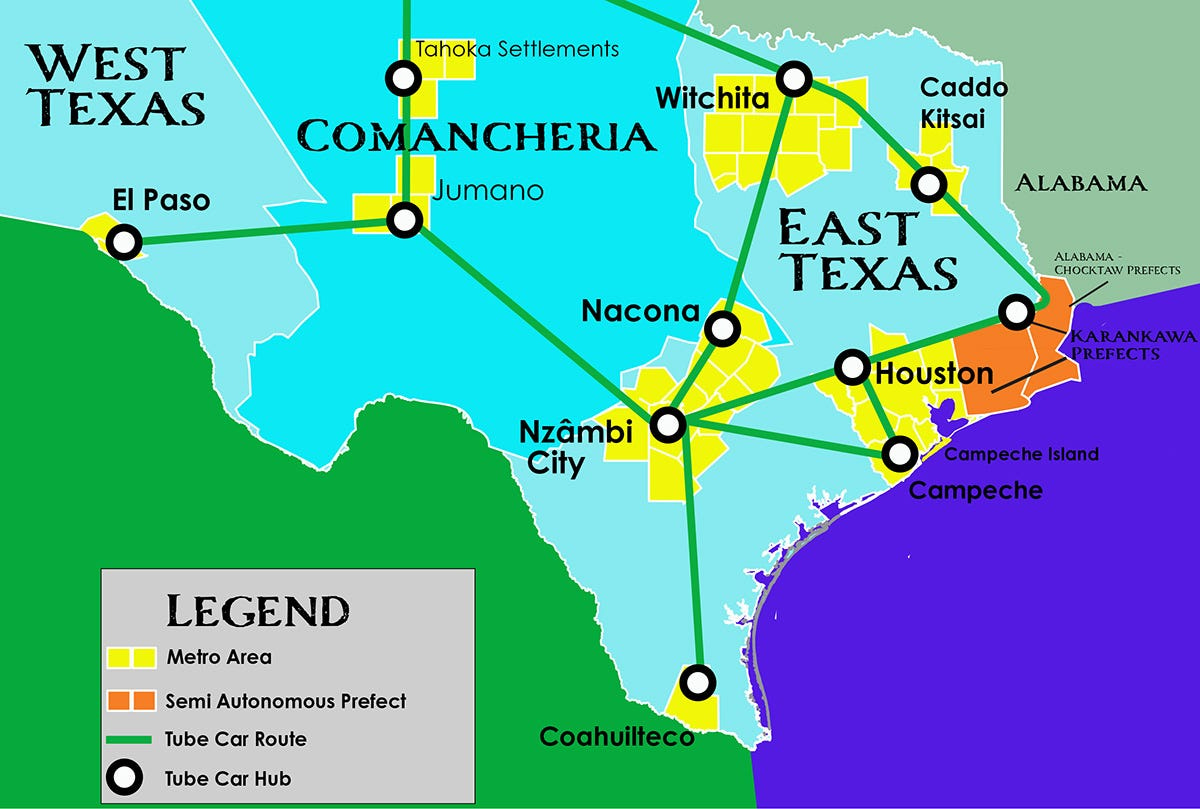

A great African nation has risen in North America. But something is… wrong. Chapter 1 & 2 of 20 in a novella based on the Restive Souls timeline.

Chapter One

This is what I see.

Summary James, an attorney for the Navasota Episcopal Congregation from Nzâmbi City, towering over a much shorter man, Sonoma Williams, the Tribune of the Congregation of the Texas Light in Houston. The two men are like two birds squawking for dominance in a cage painted by a four-sided mural lifted from the plains of Comancheria — a mural that looks alive with clouds of sediment kicked up by Comancheria warriors, one warrior leading the others in a dusty chase to the room’s door.

Williams is grieving painfully over the death of Tomas Kibende, Texas Light’s charismatic leader and his immediate predecessor, a great orator, a great tribune in so many ways, but not great, perhaps, in the ways of finance, which is why this boisterous discussion has quickly devolved into a shouting match.

James is trying to reassure Williams that Navasota’s interest in expansion into Campeche is motivated by good intent. But the grieving Williams is having none of it and is convinced that James will be able to win Synod approval of Navasota’s takeover of the Texas Light Congregation through the sheer force of money.

Williams is facing off squarely with James, who could easily fit two copies of almost any man, including Williams, inside his hulking body. If Williams has any fear, he seems constitutionally unable to show it. He is a wide man, but round, clearly no fighter. The forehead of his shiningly dark brown bald head furrows into multiple layers as he glares up at James, who says, “I resent your implications about our intent, Mr. Williams. You imply that we are taking advantage of Mr. Kibende’s death by seeking to take advantage of your congregation’s temporary financial weakness so that we can increase our power. You are fundamentally wrong about our motives.”

“Ah, the sublime ministerial intent that leaders of congregations such as yours so easily fall back on. I’m sure Joshua Brand is applauding your congregation somewhere for sending in some muscle to demand our capitulation.”

James shakes his head. “Perhaps we should loan your offices a few of our accountants to square away your finances and prevent hoodlums such as myself from showing at your doorstep.”

The insult is caught and returned, “Why bother, when they can send a brute to demand our capitulation?”

A woman in a bright festive headdress pops her head in. “Is everything okay here?” she smiles warily. “I need to be off.” Both men nod, and she returns the gesture as she leaves.

James returns to the debate, but the woman’s presence seemed to suck the violence out of the room, as the presence of congregational women often does. “My physical size has nothing to do with their proposal, Mr. Williams. But you’ll find that my legal skills substantially outweigh my physical presence if it comes to a courtroom brawl.”

Williams sighs and sits down. “I’m tired, Mr. James. Tired. Tired of congregational politics. And my unfortunate reference to Joshua Brand completes my exhaustion.”

“I come here seeking peace, Mr. Williams. We would not be seeking to merge with your congregation if we didn’t have immense respect for you.”

Williams sighs. “It is your timing we struggle with.”

“Fair enough,” says James. “Perhaps we should let a cooling-off period transpire. Would you be willing to agree not to enter discussions with another congregation if you find that your finances are as shaky as our people believe they are?”

Williams nods apprehensively. “Brand’s scorched earth policy of sucking up congregations does us no good when it comes to trusting the motives of congregations bent on acquisition. It is hard to have trust during these dark days.”

James looks down at the man in the chair, who seems suddenly smaller, and nods in agreement. Joshua Brand’s African Methodist Episcopal Congregation had acquired nearly every major congregation on the East Coast, to the point where it could match the combined financial resources of several European nations. The general consensus was that it was only a matter of time, and not a long time, before Brand would be the next Ecclesiastical Tribune of the Synod, something that did not sit well with anybody who cared about the threat of authoritarianism.

“These times try us all,” says James. “If your congregation is anywhere east of Comancheria, it seems you must ready the bastions.”

“Perhaps we have more in common than not,” Williams says, his conciliatory tone growing. “A cooling-off period, then. You have my word that we will not enter any acquisition discussions with another congregation.” William’s throat parcels out a throaty chuckle. “After all, there is Brand to consider. He could acquire us both with spare change from his congregation’s gumball business.”

“Not to put too fine a point on it, but that is why we must limit our cooling-off period. The man moves swiftly. Just this morning my phone alerted me to the fact that the AME has made a bid for one of the Seminole Caribbean Protestant congregations.”

“Nothing frightens that man,” Williams laughs. “Not even voodoo.” Williams extends his hand, and James shakes it. “Give us a week to mull things over,” Williams proposes.

Williams stands up, still clasping the hand as James says, “I think we can work with that.”

My visions don’t necessarily appear in chronological order. They enter my existence randomly with no regard to a timeline. Sometimes I must piece together clues to build the full thread. My next vision is considerably bleaker.

The woman in the headdress, a tall, striking woman of deep black skin with a First Settler’s given name, one I’m reluctantly going to admit I cannot easily pronounce, returns later, how much later, I’m not sure. She has apparently forgotten her phone. When she walks up to her computer, she sees Sonoma Williams’s door ajar but hears nothing, so she decides to investigate for no real reason other than sensing a disturbance within the utter silence of the office building.

She peers inside Williams’s office, where she notices a pair of feet wrapped in tan canvas moccasins loosely laced with dark brown cowhide strings. Both feet are pointing straight up. There are no socks on the legs, which are covered in sharp blue and red striped African silk pants smothered with an Ashanti ornamental design. It can only be Sonoma Williams. She gasps, gingerly approaches the body, and stutters into her smartphone.

But then I see more. The visions come in stealthy waves that emerge from one another like collections of ghosts. This time I see a tall, thick man wearing a squared off afro and a simple black short-sleeved shirt that is as tight on him as the skin on a plum. He is pummeling Sonoma Williams with a baseball bat etched with an oversized burnt Joshua Gibson signature that seems to punctuate itself into my vision with exaggerated importance. The man’s thin lips seem to be smiling as one side of them stretches clandestinely into a finely drawn dimple on the right side of his cheek. He appears to finish, but then, as he turns to walk away, he spins around to deliver one more blow, that smile growing as he does so, as if he enjoys it like an artfully mastered sport.

End of Chapter One

Chapter Two

Campeche Island is the gateway to southeastern Texas. It straddles the northwestern coast of the Gulf of Mexico and is home to a deep seaport that reminds some of the days of slavery that died when the nation was born out of the British victory over the Colonial rebels.

Today, the port is manned by the murderers of the Carolina Union. They are all convicts with one more chance in life. They run the machines that hoist the massive cargo holds on and off container ships from Europe, the Caribbean, Africa, and South America. They unload and move and parcel and record assets, and they are trusted to do so, to a point, with the help of a bit of electronic monitoring and surveillance. Few guards are monitoring their behavior. Somehow it works.

Campeche Port is managed by the Congregation of the Texas Light, which provides housing for the convicted murderers in a long series of tall edifices lining the shore of the Gulf.1 The prisoners are said to be well cared for and fed. The buildings they live in have no rooms of any kind until nearly 250 feet up. They are ugly concrete structures with cold gray windowless masonry.

At the 250-foot mark, they open to a series of barred windows that allow the sea breeze to waft into the prisoners’ quarters through dense interior mesh screens. The series of windows is fronted by one long parapet at each story that wraps around the hexagon structure. Each parapet is filled with a hive of weaponized monitoring electronics designed to stop the most determined escape artist, but in a non-lethal way that is rarely tested. It is said that the incentive to escape is barely present. Like all congregations, the Congregation of Texas Light does not believe in the concept of criminal punishment. Murder and rape have been the exception to the rule, and housing criminals convicted of these crimes has always been a policy challenge.

The Congregation of Texas Light met this challenge by offering to take all convicted murderers and rapists off the hands of other congregations, on condition that those other congregations were willing to surrender jurisdictional venue and prudence to the Congregation of Texas Light. This meant that all murder and rape trials were to be held in Campeche, which in turn fostered a panorama of legal education institutions throughout the region.

I was here for one of those trials. The trial of Summary James for the murder of Sonoma Williams.

I’m not intimidated by murderers. For one thing, I’m a black belt in Tae Kwon Do. That’s no safety guarantee, but it almost is when you also consider that no murderers have escaped since the Congregation of Texas Light assumed trial duties.

Many people assume Campeche Island is a scary place. It’s not. It’s like any other. People working hard, praying, and raising families. Well, most people. Not me. I’m too much of a vagabond. A man of the street. I can’t sit still in one place long enough to pray, much less raise a family. If I bring my black pork pie hat and a good smartphone wherever I go, I’m good to go. My computer guy, Trace Swanson, is my only other accessory, and he comes by way of the Net.

Trace is a Nor’easter, which is a highly educated Black graduate of a prestigious northeastern university who gets things done so quickly that it can seem like a storm coming through. Nor’easters are said to be the way they are to make up for the time our people lost to slavery before the Colonial Rebellion, but I think it’s just an East Coast thing. Trace is a deeply religious man, much more so than he would ever let on, who knows more about his African tribal genealogies than most people know about their own mother.

I was sitting in the large circular courtroom. I’ve never been in a courtroom that isn’t round. The man on trial (and it usually is a man) is always in the center, facing a magistrate flanked on each side by defense and prosecuting attorneys. A jury of his peers sits behind him, unable to see the expressions on his face. On the periphery of all that is the long, curving wooden benches where everyone else sits. The benches form complete circles except for occasional breaks for people to enter and exit.

I’ve probably been to twenty murder trials. I was a journalist for the Christ’s Union Summons, once Christ’s Union’s biggest newspaper, but now just a remnant of its former self in an age where most people get their news from the Net.

I don’t think I’ve ever read anywhere that this was how you’re supposed to do trials, this circular thing, but it’s how every trial I’ve seen works. I’ve only been to five trials outside of Campeche Island, so maybe before the Island picked up this good business, some other congregations did things differently. I could have tapped Trace to ask him, and he’d let me know, but it wasn’t important enough. Besides, five out of five other trials I had attended had done it this way. That was a big enough sample size for me.

An attractive woman with tall woven hair shaped by intricate bindings laced with small shells sat next to me. When I tipped my hat to her as if it were on my head instead of my lap, I felt like an idiot. She offered a smile that seemed to say she agreed. Her deep walnut brown skin and its ruby undertones blasted what little confidence I had into a thousand pieces. So did her cheeks. So did a set of dimples that extended from the corners of her mouth with full lips that curled upwards slightly upon her somewhat mocking smile.

“Come here often?” she asked with something that I interpreted as a somewhat seductive glance. Each of her green eyes taunted me with furiously upturned corners that accentuated a row of long, curvaceous eyelashes.

I am all too familiar with how wishful thinking can take over quickly in situations like this, so I ignored my interpretation. “As a matter of fact, I guess you could say I do,” I smiled back sheepishly, praying for the first time in a long time, asking God to remove the foot from my dry, fumbling mouth.

When she nodded, her long, patterned boubou fell gracefully from one leg as she crossed it over the other, unsettling me further. “I’ve never seen you here,” she said. “I’m a barrister with the Campeche Apostolic Congregation.” She extended a hand bejeweled with a marvelous collection of jewelry and rings I could never possibly identify.

I took it, gladly, but gently, before saying, “Longman Jones, formerly of the Christ’s Union Summons, but now just a rogue freelancer up to no good.” I decided any kind of smile would look quite foolish, so I finally managed to do something smart and remain stoic.

“Sonata Holmes,” she said. Her voice was music to my ears. “I hope you don’t mind me asking — what’s your interest in this trial?”

The truth would have been too difficult to explain. Why hadn’t God given me a vision of this woman and her question before now? And why did he give me visions of murder mysteries instead of, say, a sporting event worthy of a high-stakes gamble? “It’s an unhealthy habit I haven’t broken myself of,” was all I could come up with. At least that wasn’t strictly a lie.

“So you ran the streets on a crime beat for the Summons?”

“That and politics.”

“The difference being?”

“Exactly,” I smiled, which she returned with a devastating crescent of perfectly aligned white teeth.

Two men took positions on either side of where the magistrate would be sitting. Each was wearing the traditional peruke, indicating they were probably the barristers representing the defendant and the prosecution. Then the magistrate appeared in his wig, too, and everyone stood.

The magistrate was a tall, skinny man with a wild set of gray curly hair that was barely contained under his wig. He was also quite old, with fallow skin but lively, protruding eyes. He smiled broadly as if he was about to preside over the distribution of an amazing set of prizes before he motioned for everyone to sit. I looked at the charming woman next to me, wanting to pull her by the hand and run off with her to the nearest seductive cove, but instead, since she didn’t look back, I returned my gaze to the proceedings.

The courtroom quickly filled itself almost beyond capacity. It’s not every day a congregational tribune is murdered. The magistrate spoke. “We have before us the presentation of evidence of a grave crime against God and humanity. It is incumbent upon us all to preside over the questions presented to us with extreme diligence and care. The future of a man is not to be trifled with, as that is the domain of our only judge, God. We take on this effort with great humility, and with the understanding that it is not our right to render any judgment towards this man either way, but that by law we are forced to determine if there is an evidentiary reason for his temporary confinement until either he is rehabilitated or he is ready to move towards the Father and His grace.”

The entire courtroom in remarkably perfect unison recited, “Amen,” and the magistrate began the official proceedings.

I could bore you with those proceedings, but that seems pointless, considering that I barely followed them myself. The lovely Sonata Holmes had chosen to spend each day of trial by my side, for what reason I couldn’t fathom, so my attention toward the particulars of the trial was about as focused as a wayward boy in a schoolroom crowded with delinquents. And besides, the results of the trial were exactly as I had suspected they would be.

“Shall we get a drink?” she finally asked after the final adjournment. The wait for that question had been excruciating. Whenever did the European tradition of a man asking a woman for a night on the town get reversed here in the Union? There wasn’t a man I knew who didn’t loathe some of our unique traditions. Of course, like everyone else, I knew the answer. If blame had to go to one person, it would have to go to Shyllandrus Zulu, that illustrious eighteenth-century high priestess who was the first female Tribune of the Synod for the Carolina Union. She had insisted that the path towards men respecting the rights of women could only be paved by women taking the lead in matters of courtship. Eventually, the idea caught on, and here we are.

“I was absolutely sure you would never ask,” I replied.

“Well, I wanted to see if you were going to see the trial all the way through,” she smiled sweetly. I didn’t tell her that had that not been my intention, it wouldn’t have mattered — that it would have become so as long as she was by my side on the uncomfortable wooden bench during the weeklong trial.

We walked along the Campeche Malecon, where we found a charming little drink establishment exuding a pleasant mélange of First Settler and Spanish foods. A waitress brought a menu imprinted with the words, “Welcome to the Campeche Baptist Ministry Congregation” on one line and on the next, “Drinks and delightful eats for the soul”. My mouth curled downward as if to say I had never heard of this congregation. I assumed that it was a small congregation local to Campeche Island, maybe one that specialized in the hospitality industry or convict groupies.

We ordered a couple of beers with an appetizer of buffalo meat tomatillo tamales.

“The sentencing seemed a little harsh,” she said to me after the tamales appeared. I unwrapped the corn husk. Then I used my teeth to tear at the tortilla and ate the tamale from its open wound, much of which spilled out onto my fingertips, which amused her. “You don’t like the tortilla?”

“Hate them,” I said. I extracted the tamale filling with my lips and tongue, trying not to look like a savage, then set down the damaged goods. “It’s really a pretty ordinary sentence, isn’t it? Forty years takes him to old age, where he will live a comfortable life regretting the incident in a rocking chair.”

“But he didn’t do it,” she said.

“How do you know?” I asked, intrigued.

“Because you do,” she said. I hid my alarm. She couldn’t possibly know what I knew.

I raised my eyebrows. “Go on,” I urged.

“I’m an empath. I may not know what you know, but I can sense it.”

Oh, dear God, I thought to myself, knowing I was in way over my head with this woman.

I ate in silence for a few moments.

“Hey, I’m sorry,” she said. “That should have been the very first thing I ever told you about myself.”

I shrugged. “It’s okay,” I said. It really was okay. Everything about this woman was okay. “And the first thing a barrister should do is identify yourself, so you’re good. But anyway, here’s the thing. The way I know, what I know. It wouldn’t make sense to you, or anybody else.”

“But you’re certain, and that’s the key takeaway here.”

I nodded. “Yeah. I’m certain.”

“Do you know who the real killer is?”

“I do not. I would recognize him if I saw him. But that’s about it.”

“Well, we should find him.”

“We?” When I had asked her after first meeting her in the courtroom what her interest was in this case, she had said it was routine for her congregation to monitor murder trials. This seemed like quite an escalation in that interest.

She ate her tamales perfectly. I began to think that Trace had designed her from one of his software projects, knowing exactly everything I liked in a woman, but then I remembered he didn’t know much about my love life, or, more accurately, my projected love life. She nodded eagerly and said, “Uh-huh.”

That gave me the feeling that this was all going to end in a wildly improper way, probably leaving me morose and bitter. I didn’t care. “It’s a big country,” I said. “I don’t have the first clue where to start looking.”

“I guess I don’t need to tell you that a barrister’s work is often a lot like detective work. That is when we’re not looking up obscure laws on city parking lot allotments and other mundanities. I’ve laid off the question but now I gotta know. How do you know who the killer is? If you didn’t witness the murder yourself.”

“I kind of did witness it. But not in a way that any lawyer can use.”

“Uh-oh,” she said, finishing her last tamale.

“What?”

“You’re one of those. Do you hear voices in your head, too?”

“Only after I eat tortillas, so you’re good. Don’t worry.”

She smiled at that. “Has this ever worked for you before?”

“This?”

“Visions.”

She knew too much. I wanted to end the conversation and leave, but then I looked at that ravishing face and decided you only live once that you remember, so I chugged on. Literally. I quickly drank down a good six ounces of beer in one gulp.

“It’s why I quit the paper,” I said. “Most of us quit because the Net has killed off so many print pubs, but not me. I’d a stuck with it if not for,” and I made a gesture with my fingers in the air before pointing to my head. “I’m four for four so far.”

“Impressive.” She had barely touched her beer. I was ready for a second. “Okay, well, I’m sold. I assume you’ve let your computer guy know about this and given him a description to work with.”

“Wait you said you’re an empath, not a mind reader.”

“Everybody in your line of work has a computer guy. Or girl. But something tells me with you it’d be a guy.”

“Good God, why do you think that?”

She shrugged.

“And what’s my line of work?”

“I dunno. What do you call it?”

“Since I don’t get paid for it, I guess I call it dopin’ the system.”

“Works for me.”

“And no. I haven’t told my computer guy yet.”

“Does he know about your special, umm, talent?”

“It’s not a talent. It’s a curse. It’d be a talent if I could benefit from it in some way. He knows, sure. As for him knowing about this particular vision, I’ve been waiting for the verdict and sentencing of this case to come in. No sense pursuing it if he is acquitted.”

“Good point. But I still don’t get why you felt the need to attend the actual trial.”

“This is the fifth one. Fifth vision. I guess I just started out doing it this way, and it’s what I’ve been doing every time so far.”

She nodded at that. “What happened with the others?”

I told her. I began with Screams McShane, an Irishman with an accent so thick nobody could understand a word he said, who had a temper shorter than an ornery toddler. He had been convicted of blowing up a congregational bank in Christchurch. But in a vision, I saw three German Presbyterian militiamen training in upper New York state, then those same guys wandering around the docks just those few hundred miles south in Christchurch on Manhattan Island, then, just like a dream that scatters around with no discernible logic, those same guys blowing up the bank. It didn’t make any sense that McShane was convicted. He was nowhere near the scene of the crime. Two people were killed, including a small boy. Many folks wanted to reintroduce capital punishment.

There was no way to effect a change in the way the judicial system was going to process this case based on my “observations.” So I did the next best thing. I kidnapped McShane, much to his surprise and indignation, on his way out of court before sentencing. I drove him up to the Iroquois Northlands, where I had a friend who could provide McShane cover for a time. McShane was a master carpenter, so his skills quickly began to serve him well in a place where many people preferred a simple life off the grid. The last time I checked on him, he had adopted an Iroquois name and was on the verge of marrying into a family up there, happy not to be sent to an internment house on an island off the coast of Texas.

When I finished telling Sonata about the three others, I realized I had just told a high-powered attorney that I had broken the law several times. I began to think about which congregation would get hold of me for rehabilitation. So much for my lifetime dedication to avoiding the Bible.

“I was not expecting such a…” She was clearly at a loss for words.

“Rogue? Well, I did tell you.”

“Yes, but I guess I thought you were flattering yourself. But you clearly mean business with this stuff. But can I ask you?” She didn’t wait for my reply. “What if your visions are wrong? What if you’re helping people who belong in an internment house?”

“They’re not wrong.” I was steadfast in my reply, and in my belief.

NOTES

This short novella was unplanned. It popped out of my head when I started researching for Restive Souls. I cranked it out in 2021 after an embarrassing number of drafts (maybe 5 or 6, I’m guessing, so it’s almost still in first draft form!).

This novella takes place in an alternative North America that celebrates diversity, avoided genocide, and corrected the mistakes of slavery as a side-effect of a failed Revolutionary War. As such, although no human endeavor can avoid tragic error, it takes place on a much less dystopian continent than our current experience.

The world represented here is much larger than can be conveyed in such a short book. This world is more fully represented in a trilogy called Restive Souls, which begins in the late 18th century. The novella is a potboiler meant as an easy, quick read, whereas Restive Souls is more serious business, and is in an endless state of edits that I’m hoping to complete before the year 3000.

But the main character of this novella, Longman Jones, told me he wasn’t willing to wait for me to finish that novel. Maybe that is in part because he makes no appearance at all in the larger work.

But he is a restive soul, and he needed to get out of my head. As some of you know, my head literally (yes, literally) explodes when there are too many characters living in it.

Other Chapters

Thanks for reading!

What’s the name of the “Gulf” in this timeline? I can tell you what it isn’t called.

I’m glad to see Texas being put to good use. And eating tamales from their open wounds—love that description.