I’m in freefall. Moses, who runs the canteen, says we are nearly out of maple syrup. Highway 1 is closed again because of another rock slide that, this time, the authorities are unlikely to address.

Trigger warnings: Language, parental loss, and talk of suicide

By my count, California has fixed Route One a dozen times in just the last few years. The road is broken beginning on the other half of the slide, so nobody is driving into town for supplies anytime soon.

Eva, who has traditionally extracted maple syrup from the Big Leaved Maple trees that help fill the forest here, left last year when she married a professor of shaman studies from Bemidji State University.

I guess since I’m the one who will miss her maple syrup most, I’ll be the one who learns how to do what Eva did, although I don’t know the first thing about extracting maple syrup from anything other than a bottle.

“Caltrans ain’t fixin’ her this time,” says Moses about the road out of town as we sit at the canteen’s massive wood dining table. We’re the only two in the large eating hall, so I feel like I’m sitting next to the one guy in an empty amphitheater waiting on a Dead concert.

I’ll note here that I haven’t seen a Grateful Dead concert for thirty years.

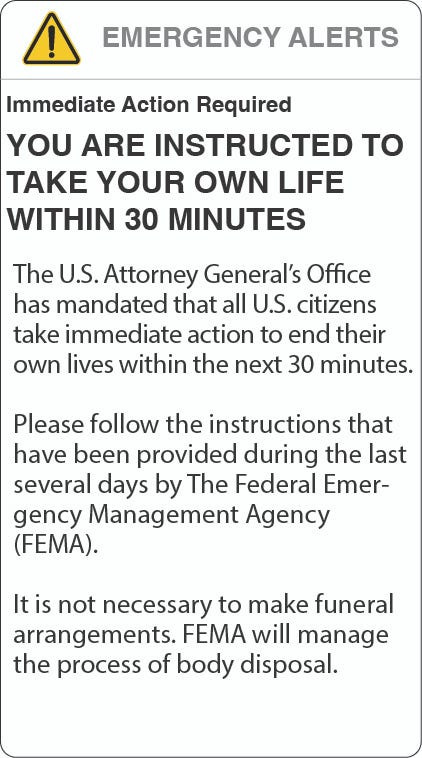

Moses shows me his phone, since I don’t have one.

“When did these dudes start hacking government emergency services?” I ask. “We’ve been seeing these alerts for weeks.”

Moses shrugs two bony shoulders that look like you could hang your hat on. “This one’s different, though, see. The other ones were instructions on exactly how to off yourself. Very specific.”

I nod, flick some hair out of my eye with a hand. “And not one of them says to jump into the canyon. Lame.”

“Or drive off Highway One,” laughs Moses. “Easy enough to do in these parts. I mean, it’s kinda how I wanna go out.”

I change the subject. “We’re kinda low on medical supplies, too, aren’t we?” I ask.

“Nah,” says Moses. “We okay.” He ruffles the tall, oblong mound of his salt and pepper afro like he does whenever he can’t think of a way to expand on a comment.

I nod appreciatively. I love Moses so much that sometimes I just want to take his scrawny black hand and kiss it randomly, even though, according to him, I’m “freakishly hetero.”

“It’s the other shit we need. Flour and such,” says Moses.

“We can make flour,” I say.

“We can.”

“I mostly want some maple syrup.”

“We gots some, dumb ass, chill.”

“Not much.”

“Quit your bitchin’. The world’s ending.”

“Is not,” I laugh.

Moses waves his phone at me. “How come the government ain’t stopped this shit then?”

The current alert on his phone has instructed every American to commit suicide. Obviously a hack. But it has taken over his phone. He can’t navigate away from the alert even if he reboots his device.

We had talked about this when the earlier alerts were sent out. We decided there was a fifty-fifty chance that people would follow the instructions.

“Shit, I dunno, Mo. Who am I, Bill Gates?”

Moses shrugs.

“I don’t even know who’s president.”

Moses nods.

“And don’t fucking tell me, neither.”

“Wasn’t bout to,” he smiles.

“That’s why I live here. Get away from all that shit.”

“Yeah, I know my brother.”

When he puts his hand over mine, it looks like an ad for racial harmony. My hand looks like it’s about twice as big as his and has freckles the size of his fingernails. “Unhand me, knave,” I kid. I pull my hand away and flick hair out of my eyes again.

He shoves the phone’s display in front of me. “Will you look at this shit?”

“No. It’s why I don’t have one. Damn things are making people crazy and turning them into automatons. Malthus is gonna be grinnin’ ear to ear one of these days.”

Moses shoves the phone’s display so close to me that it nearly hits me in my right eye.

“Maybe he already is,” says Moses. He withdraws the phone from my eyeball, but I can tell by his expression that it is with great reluctance. “We could take Elsa’s donkey into town for supplies.”

“How long will that take?”

“I dunno, man. Probably a little more than a day in, same out?”

I shrug.

“That a yes?” he asks.

I nod.

Where we live, you used to be able to see an arm of the Milky Way if you could find a big enough clearing in the woods or if you camped out along the Pacific side of the mountains.

In recent years, even in the mountains, the urban halos of San Jose, Santa Cruz, and Santa Barbara have washed out most of the stars from that part of the galaxy as if trying to obstruct the few remaining signs of God.

As we camp for the night in the eastern Santa Lucia foothills, I can imagine viewing the arm of the Milky Way over the ocean, suddenly wishing I was there.

“Never seen it this dark,” I say as we set up our tents.

“Yeah, man, it always seems dark up here, but this here, this is different. I think we should camp on the other side when we get back.”

“We’ll be almost home then,” I say.

“So? How often do we get to see the Milky Way in all its glory without a long exposure and a goddamned light filter on the camera?”

“Good point. I bet we could see it tonight if we were on the other side.”

“It would be a glorious sight. I bet the whole West Coast is in a blackout,” says Moses.

“Mass suicide will do that,” I chuckle grimly.

“Don’t they have computers to keep the lights on for a while in the event of worldwide catastrophe?” asks Moses as he bends his long, gangly body down to drive a metal tent stake into the ground.

“Yeah, probably,” I answer, fishing for a stick of venison jerky.

“I used to shoot the sky a lot when I lived up north in Bonny Doon,” says Moses. “I’d take these long exposure photos of the Milky Way.”

“I remember one you took from the Bridges.”

“Dude. I was proud of that one.”

“I was, too. I was like, that’s my friend. He took that.”

Moses laughs at that. I’ve always thought that his laugh sounds like the bray of Elsa’s donkey, whose head is bent down as her big lips pull roughage from the ground into her gullet.

“Crack a dawn?” asks Moses.

“Crack a dawn,” I reply. We fist-bump as I climb into my tent.

We reach town after a more strenuous hike than I had anticipated. Some of the switchbacks were still muddy from the same rains that had caused the rock slide.

There is only one store in town. It’s called ‘Gus’s Feedlot.’ It carries everything from lumber and paneling to veterinary-grade horse feed and some of the best ribeye steaks on the West Coast.

The place rents farm machinery, ladders, and small backhoes, among other things. Some locals insist that Gus had at one point even squirreled away a snowmobile somewhere, maybe in the big metal shed behind the building, just in case the Santa Lucia mountains decided to turn into the Sierra Nevada someday.

The building isn’t any bigger than your nearby Ace Hardware, but it is stuffed with more merchandise than you can find on Amazon.

Since you can’t walk around the store without knocking something over when you’re wearing a backpack, which most customers do, there is a wall near the entrance filled with large square nooks to store your backpack while shopping.

There’s no system for this. You don’t get a number or anything from a clerk. You shove your backpack into a nook and hope it’s still there when you check out. It always is.

We arrive at Gus’s at about nine am, I reckon, although I don’t have a watch. I can tell by the sun what time it is. Gus always opens his store by seven am at the latest, and by nine, I figure the place should be bustling.

The store’s large screen door is ajar. When we push it open, its hinges squeal loudly into the store’s dark interior like the cry of an unknown animal wrestling hopelessly with a sadistic predator.

The place is empty. I know this even though I can’t see much more than empty backpack nooks against the wall along the entrance.

“Yo!” Moses’s voice rattles along metal frames stretching across the ceiling. Something flies around somewhere above, its wings beating quickly like a bat until it halts with a soft clang that resonates meekly against the ceiling’s metal frames.

Moses tries again. “Somebody?”

He looks at me. I don’t know what to say or do, so I shrug.

Moses pushes through two circular racks of raingear that are too close together to sift through for anyone but the most determined shopper.

The store smells like leather, varnish, and rubber. Usually, you can instead smell a kitchen that arrests the other odors with bacon and coffee at this time of the morning.

I try my own callout: “Hey!” After a beat, I try again. “Anybody here?”

Moses pushes ahead while I gaze at my surroundings. Up, down, across, in front, to my sides, my eyes canvass the eerie quiet.

Ahead of me, I hear a loud crash of metal against the floor.

“Fuck me!” I hear Moses yell.

I push my body between two circular shirt racks, one carrying heavy flannel shirts, the other something that looks like children’s sleepwear. I don’t stop to examine exactly what kind. It’s almost too dark to tell, anyway, unless I shove my face into them.

Whatever has fallen to the floor next to Moses has triggered a cascade of additional bedlam. When I reach him, I turn on my camper flashlight to see what appears to be hundreds of Stanley cups on the floor, many of them still rolling slowly as if they were all in a disordered parking lot searching for a resting place.

Moses looks at me and shakes his head. “It was beautiful,” he says. “A work of art.”

“What was?” I ask.

“This stack of Stanleys. The pyramid must have been twenty feet tall.”

“Huh,” is about all I can manage.

Moses turns to face me, puts his hands on my shoulders. “I destroyed it, Jack,” he whispers. His sorrow sounds genuine, like he had killed a friend’s sister. “My lack of respect for the artist won’t go unnoticed by the karmic gods.”

“What the hell is going on here, Mo?”

The sound of two small feet running in shoes with hard bottoms prevents his answer.

The next sound is a terrible groaning that fills the store’s interior with a deep, ghostly reverberation from the ceiling to the floor and seemingly back again.

“Moses?”

“What, my man?”

“Do I need to ask the obvious question I’ve already asked? You know the owners better than I do. What are they up to? Where are they?”

“I dunno. Follow me.”

He turns his phone light on. We wind our way between aisles full of canned tuna, flashlights, jerky, camping equipment, fishing poles, folded mountain pants, Yeti coolers, sandals, ascenders and pulleys and carabiners, and Voodoo potato chips, which hang from the small hooks of a metal snack display against the wall next to a bathroom.

Moses bangs on the bathroom door. “Betchya that awful sound was from here.”

“You’re saying that the sound that bellowed all across there,” I point and wave across the ceiling with my index finger. “That sound, came from here. The women’s bathroom.”

“Yeah. Pipes. Hot water. Someone’s in there.” He bangs again.

“Oh.” I approach the door and open it a little.

“Dude. Privacy,” Moses admonishes.

“Yeah, well, if it’s a kid, she is gonna be scared. Let’s just get that part over. You heard that running, right?”

Moses nods.

“Anybody in there?” I ask the door. I open it a little more. “Hello in there? I promise you I am not Slenderman.”

“What the fuck is wrong with you?” Moses yells in a whisper.

“Just trying to break the ice.”

“The fact that you have never been around kids is plainly obvious.”

“That is not true. You’ve even met my niece.”

“Yeah, sweet kid.”

“See?”

“Also? Kinda spooky.”

“Shut up and say something to her.”

“How do we know it’s a her?” asks Moses.

“I’m a guessin’ this?” I point to the sign that says “Ladies” on the door.

“What if he can’t read?”

“Shit, Moses, just say something. Anything.”

“Come on,” he says, “Let’s just go in. If she was piddling, she’ll be done now.”

“See? A girl. You just said.”

Moses sighs and steps gingerly inside. I flip the light switch on the wall, relieved that it works. “Why didn’t we do this in the store?” I ask.

“Didn’t even think about looking for the lights… oh.” A young girl, I’m guessing at that moment about ten years old, is sitting on the floor in the corner whimpering under a hand dryer. Her straight black hair is hanging over the dark olive skin of her face.

“Hey,” I say gently as I stoop down in front of her. “Where are your parents?”

When she brushes the right side of her hair away from her dark green eyes, I can see she’s been crying for a long time. The tip of her tongue pushes out the corner of her lips as she pulls a phone from a pocket of her khaki pants. Her shaking hand tries to hand it to me.

“I’m sorry, I don’t understand,” I say without taking the phone.

She sniffles, turns the display of her phone on, then tries to hand it to me again.

This time, I accommodate her. It’s the same message Moses and I had seen before we hiked to the store. I stand up and hand the phone to Moses.

“Shit,” he says.

“Yeah,” I reply with no emotion. I have none right now. I’m mostly just worried about the kid. The possibility that her parents actually followed the instructions and left their child behind is too extreme for me to grasp.

“Where is everyone else?” I ask as I hand her phone back to her. As if she’d know.

But she points to the screen of her phone. Finally, she speaks. “I think they’re all gone,” she says through a quivering voice.

“You know this is kidnapping, right?” says Moses. “And we even got a kid.”

The cold breeze from the north on this early evening bites into my cheeks. “She’ll vouch for us, if there’s anyone around to vouch to,” I respond. “Besides. We asked. Do you want to come with us? I heard us both ask, like, ten times. She nodded her head about fifty times.”

“None of us had a choice, really,” says Moses sadly. “Including her.”

Moses and I haven’t talked much to this point. We’ve been making sure Inés, the young girl we’ve taken with us, is comfortable. She’s a hardy kid, though, someone who has clearly been through her share of hikes already.

She’s been spending most of the time about ten steps behind us, tending to the donkey, which she has apparently decided is now hers.

“You don’t think anyone from the compound did it, do you?” I ask, wondering about the immovable alert on her phone and how we might find a home for this poor girl.

“Elsa, man” says Moses. “She seen the alert. She was fine. She laughed about it. Said the same thing as we said. Said, ‘them numbskulls will do it, too,’ but she was joking. I think.”

“And Annie and James were chopping wood when you were getting Elsa’s donkey,” I agree.

“It’s why we’re all here. To not be a part of that world,” says Moses.

We need to try not to talk about these kinds of things within earshot of Inés, so we talk instead about camping on the other side of the mountain so that we can all look at the Milky Way. The night is dark and crystal clear again.

We both agree that Inés might like that. If she can like anything right now.

“She holdin’ up okay, really,” says Moses, reading my thoughts when we reach the summit and begin our descent.

“Yeah she is. Holy shit, look at that.” I point at the thick filament of the Milky Way stretching from the horizon up across the northern sky. “This ocean view is going to be epic.”

We wave Inés over to us. She helps us provision the donkey like she’s done it a hundred times, then joins us on a mossy rock on the edge of a stable cliff so that we can all enjoy the surf crashing against the rocks below. It’s an intense surf, one that would normally attract surfers if the shore was softer and not the jagged pile of rocks it is in these parts.

Inés grabs my elbow and points below, to angry whitecaps crashing against the sharp boulders.

There are dozens of bodies strewn across the shoreline, where white crested waves foam up against the rocks and rubble. I can’t possibly recognize the bodies’ faces because they are too far away, but I can’t help but think I know some of them from town. Bizarrely, macabrely, I find myself hoping they are tourists.

They now exist as nothing but distant footprints of former lives stamped into the rubble of the violent shore, which rolls a wave over one of them and drags it into the ocean like it’s feeding an invisible leviathan.

Moses looks at me with a tear strolling down his cheek. He pulls his phone out of his vest and throws it down the cliff toward the new gravesite.

Inés stands up, looks at her phone, and gives it such a mighty heave that it reaches the lapping water and disappears into the dark, roiling ocean.

NOTES

This short story first appeared in The Kraken Lore in June 2024. Seems fitting for these times, does it not? Thank you for reading.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, did you know there’s a 911 type of number you can call? In the United States and Canada, it is 988.

Call 988 if you are or someone you know is having any kind of suicidal thoughts.

There is help out there!

Here is a website with numbers for other countries:

Suicidal Crisis Support - IASP

If you are feeling suicidal, you are not alone and there is support available. You deserve to feel supported.www.iasp.info

This is exquisite: "They now exist as nothing but distant footprints of former lives stamped into the rubble of the violent shore, which rolls a wave over one of them and drags it into the ocean like it’s feeding an invisible leviathan."

Also, the tear "strolling down" is very satisfying.

Don't know if you've ever seen the episode "CONTINGENCY" from the "Local 58" analog horror series, but this reminds me a lot of that.

And, yeah, I think there's a lot of people right now who'd do whatever the government told them, ridiculous as it sounded.