How I Survived Workplace Ageism

It should have been a great interview — instead, I walked out

Several years ago, I went through a round of phone interviews with a tech startup in Austin. The fit seemed perfect. I possessed the deep layers of software skills they were looking for, and I was ready to try my hand at a startup after several years of working at bigger companies.

My prospective employer was a software services company that integrated visually pleasing graphs into comparative analysis tools measuring the efficacy of medical treatment modalities. When healthcare professionals saw an interesting data point on a graph, they could click a point on the graph to drill down for details.

That’s not particularly exciting, right? But a lot of successful tech companies establish niche products like this. In my initial discussion with him, the startup’s founder rattled off several large healthcare providers who had already signed contracts. Profitability seemed realistic, which meant that any potential equity might mean something.

So, I was excited.

The startup principals used phone interviews to help establish my qualifications. One of the interviewers was the aforementioned company founder, who possessed the tech background necessary to establish whether proceeding would be a waste of time.

By the time the interview was over, there was mutual excitement. It was both a personality and tech fit. He next had me interview with one of his engineering leads, who dug a little deeper, and in a respectful and personable way, tried to corner me on a few issues.

That’s pretty routine in tech interviews. Most tech interviewers are not necessarily trained in the nuances of interviewing, but they figure it out because they do it so often. Engineers who conduct interviews for tech jobs typically try to focus on whether your knowledge is picked up from a few tech readings online or gleaned from experience. They become pretty good at it.

The result of my interview with the tech lead was similar to the interview with the company founder. I could feel a sense of mutual respect and appreciation. When I was finished, I felt certain they’d call me in soon.

The founder called me back less than an hour later. “We’re really excited to meet you,” he said.

Most Austin tech startups are filled with people who don’t know what life was like before smartphones. I was already approaching my sixties, so the only reluctance I had was working for a bunch of kids (ageism can work both ways).

But it wasn’t like I hadn’t already been doing it. My previous supervisors were often about ten to twenty years younger than me at the bigger companies I had worked for.

The worst-case scenario in my head was that they’d lowball me somewhat on the offer and try to compensate for the difference with an equity package. I was fine with that. I thought the company had a chance to go places.

The next step involved running through the usual gauntlet of tech interviews.

In my experience, tech software teams put prospects through a series of interviews during the hiring process.

There’s always at least one technical interview, which in those days often meant answering problem-solving questions on a whiteboard. I’ve had interviews with just one or two people, but sometimes as many as seven have sat in a room peppering me with questions about whether or not I could write some pseudo-code to demonstrate that I knew my way around software patterns and Java classes1 or whether I was flummoxed by the JavaScript this keyword.

In this case, they sent me a software test to complete online under the dutiful eye of one of their engineers. It was an easy one, and I quickly moved on to the next stage of the gauntlet.

The next stage was a phone interview with about five or six software engineers. They asked me about some of my general coding philosophies and how I’d handle a variety of technical problems that might come up.

This went well, too, so it was on to the next round.

When I visited their offices, I didn’t see the usual playthings we often associated with tech startups in those grand old days of company chefs. It was a pretty spartan place, probably because their focus to that point was getting software code released. I knew they had secured Series A funding,2 so I was glad they weren’t spending it all on wall art.

I was confident about this next round. It would be a technical interview involving about seven software engineers, including the founder and tech lead, but I knew my stuff.

Fifteen or twenty years in the business troubleshooting code, encountering the clever ways users have of turning your system into mush that aren’t captured by QA (Quality Assurance) tests, I proudly felt, was a bonus that is hard to put a price on.

I had already spent years working for companies that valued my kind of experience. I wasn’t ready for the reaction of the room when I walked in after the young receptionist accompanied me to the door and opened it with a slightly sardonic smile (which I attributed to my overactive imagination).

The chattering of the room ceased. Jaws dropped. Faces fell. And hey, I don’t mind saying, this in spite of the fact that I looked pretty good for my age.

But they weren’t looking for an older version of Ryan Gosling (okay, I didn’t look that good). They were looking for someone…

…young.

Or, at least not someone who was obviously past the age of 50.

When I sat down for questions, the founder, still in shock, asked the lead engineer if he was ready to ask some technical questions.

Meanwhile, I wanted to check my shirt to see if parts from my lunch or maybe a bit of spittle had found their way to my person before my arrival. You know, like some old guy.

What, I wondered, has them so aghast? Although, I had a suspicion of what was wrong.

“I got nothing,” the lead tech replied without emotion.

The founder asked the young woman next to him. She shook her head no. He asked one more person, who replied with, “I’m good, thanks.”

The eagerness they had shown previously to talk tech, probe me with questions, or even share war stories disappeared as if the white hair on my head had spread a bizarre muting disease.

I then did something that I could never have imagined myself doing. I stood up and motioned to the whiteboard.

“Do you mind if I just do a 30-second demo?” I asked.

Looking a little surprised, the founder said, “Sure, no problem.”

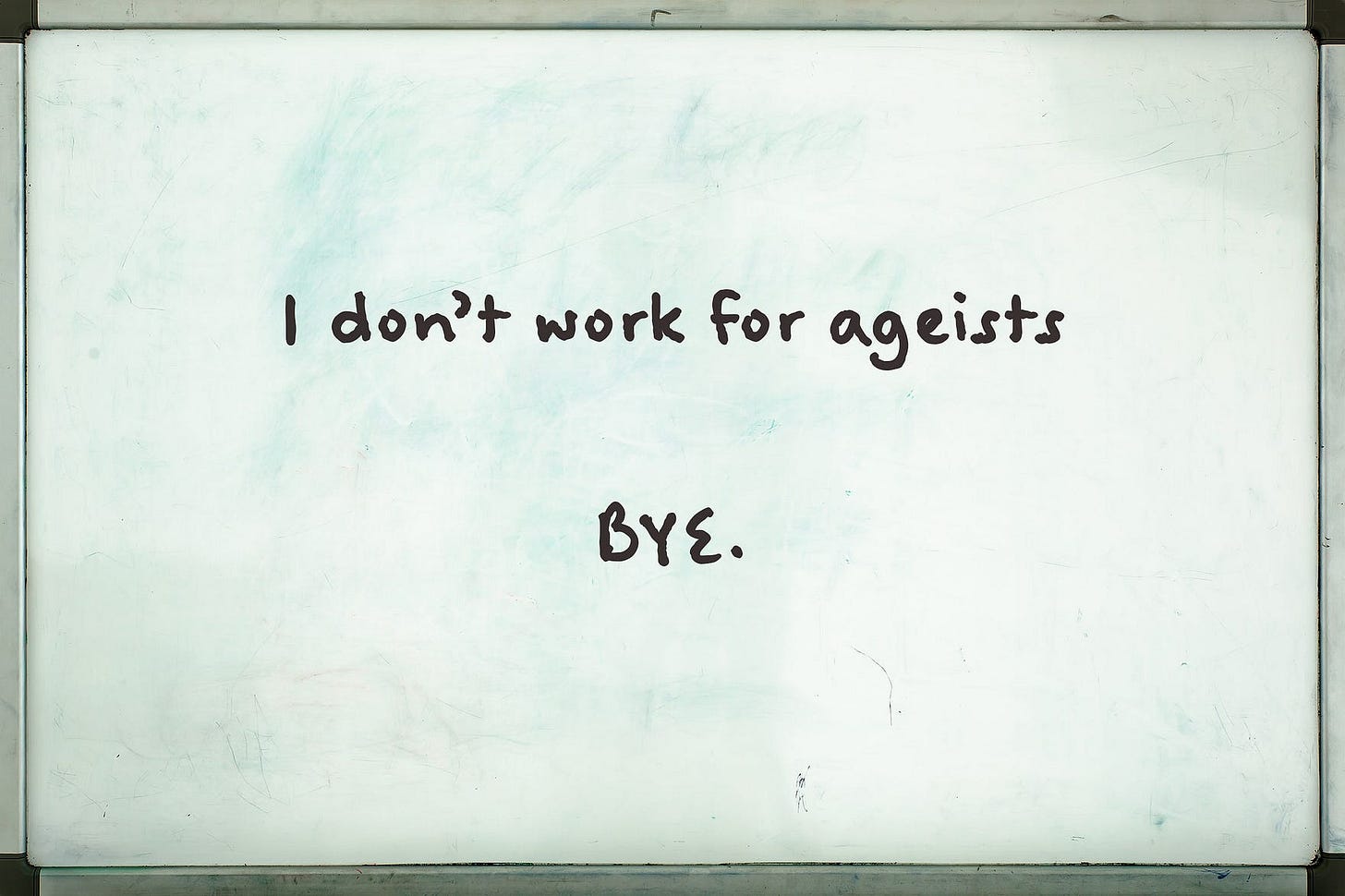

I walked to the whiteboard and wrote what you see in this image:

Except for the top part. I didn’t have the courage to write that top line, but it’s what I wanted to write.

Instead, I just wrote “Bye,” and left the room without looking at anyone.

I still regret not writing that first line. People who know my personality know that it’s not like me to be confrontational in that way, especially without a lack of firm evidence. But it’s how I felt as I walked out of the interview.

A lack of firm evidence is the essence of trying to deal with ageism. Unlike some of the other “isms,” ageism is a little harder to establish. Most of us older types know that when someone says we are “overqualified,” it often means we’re too old for the person making that declaration.

Because of that, the only real mechanism older people have to deal with this problem is to cope.

This true, but anecdotal, story is an extreme example of the most important lesson I learned in my nearly 50 years of various kinds of employment: Interview the interviewer.

I moved on and interviewed with another large company, where I took a job with a supervisor who valued older employees.

I interviewed him, too.

I’ve made a habit of interviewing my potential supervisors almost as if they were job applicants.

My favorite question is a form of, “What brought you to this fine institution?” This kind of question opens the interviewer up because successful people usually like to talk about themselves. In the case of the job I finally landed, I learned a lot about the hiring manager, including his distaste for how women are often treated in corporate environments.

I was sold.

There’s a lot of ageism out there. No doubt. But we can navigate those troubled waters with some deft psychology of our own to help us find a proper work environment.

Many of us offer so much experience that companies do themselves a lot more harm than good by avoiding us. We can use that experience when we job hunt, too, by looking people in the eye and using our hard-fought wisdom to determine if their place of employment is a good fit for us.

Notes

The tech startup I interviewed with no longer exists. My equity would have been squat. I honestly can’t even remember their name now, but when I looked them up several years ago, I saw that the company had expired.

Image of Ryan Gosling by Raffi Asdourian, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons; aged by author in Photoshop (spoiler alert: my attempt to make Ryan Gosling look bad by ageing him had no real negative effect).

This article first appeared on Medium’s Crow’s Feet publication

Thank you for reading!

In this case, “classes” refers to discrete reusable objects you can use in Java code, not a place where you listen to teachers.

Reiff, Nathan. 2015. “What Is Series Funding A, B, and C?” Investopedia. 2015. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/102015/series-b-c-funding-what-it-all-means-and-how-it-works.asp.

I had exacly the same experience in Silicon Valley many many years ago. Went through all the remote interviews layer by layer, everyone was excited, then flew down (from Canada) for the in person with the whole team, walked into the room and everyone was talking. The room fell totally silent. The rest pretty much as you describe, except being desparate I didn’t think to walk out…

Probably a common story, especially in your line of work. It's hard for me not to see a real leadership problem here: the founder passed on asking questions, setting up the others to follow suit. Had there been some wisdom there, he/she would have asked some robust questions intended to set up the others present to probe deeper on those topics, or simply to signal that this was a serious interview. Seems like the leadership/management style did not translate to a successful way to run a business.