Here's Why Young People Aren't Reading Your Substack

Cliff's Notes: They can't read

You may have noticed lately that Substack has decided to become a video broadcaster. Why, the intrepid writer (and reader) of elegant prose asks, is Substack doing this to us? Substack has traditionally been one of the internet’s primary sources for long-form, substantive, and written prose.

Few sanctuaries remain for the devoted literary traveler. There’s Substack, Medium, maybe Patreon, and a few others I won’t bother mentioning because I don’t frequent them.1

I’d prefer it if Substack would settle into its niche and ditch video. My reasons aren’t based on some old guy get off my lawn, “I’m not here for video!” rant. For me, it’s a practical matter: I read about ten times faster than I can watch a video. To use the word “literally” in a way that actually makes some sense, I literally2 have better things to do with my time than watch someone fidget while they’re chitter-chattering away about stuff I’d rather read.

If I spend an hour watching a Substack video, that’s an hour I could spend filling my head with about ten times the same information by reading. This is because when I was in first grade, I was told by my first-grade teacher that I had a 12th-grade reading level. In other words, I’ve always been a fast reader.

The reason for that wasn’t because I’m brilliant. I'm rather average intellectually. I’m not ashamed to admit it (it’s God’s fault, not mine, so why should I be ashamed?). The reason was that my parents, who were not Ivy Leaguers by any means,3 had a family room with bookshelves stuffed with old classics.

I became a voracious reader at such a young age that I don’t remember not reading. My early forays into the written word were things like The Hardy Boys (not a classic in the true sense, of course), Gulliver’s Travels, Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz and its sequels, and my favorite, A Christmas Carol, which I read every Christmas until I was a teenager.

During the first few years of elementary school, I graduated to more complex fare, such as The Brothers Karamazov and Dante’s Inferno.4

My parents owned an amazing old edition of Dante’s Inferno illustrated by Gustave Doré. I was fascinated. Those other old books were amazing, too. All of them, even A Christmas Carol, were brimming with the kind of illustrations that triggered a young mind like mine to explore the words that surrounded them.5

So. I was nothing special. My reading environment was special.

I started writing when I was in third grade.

By the time I was in fifth grade, I was walking around handing out 100-page palm-sized comics to my classmates. It was my first “book series:” The Adventures of Dr. Maums, about a ruthless galactic emperor who bore a suspicious and uncanny resemblance to The Addams Family’s Cousin It (I left off the hat because I was very creative).

My classmates didn’t respond by bullying. They ate the books up. The little books, made out of notebook paper, were often returned to me in tatters, but the good kind of tattered. The “this has been read by a lot of people” kind of tattered. It reached the point where my fellow students started asking for them in advance: “When’s the next one?!”

Encouraged, I wrote about 30 of them.6

Avid, devout readers all have similar tales. I’ve seen them told. These are tales missing from the lives of many of today’s young people.

In the before times, before the American people twice elected a man who has never read a book cover to cover (“I read passages, I read areas, chapters, I don’t have the time.”),7 there were great expectations about student literacy.8

Somewhere down the road, and we can argue pointlessly about exactly when and how, American universities started gearing their curricula to the pursuit of the great American greenback. Student success was measured by MBAs, computer science degrees that could land graduates in the bourgeoning tech industry, and the establishment of other points of interest along the great and wonderful capitalist road.

To be fair, if they hadn’t shifted toward employment prep, most American universities would have disappeared. Public high schools quickly followed the same course.9 They pivoted away from humanities and even shop class to college prep. Since colleges were all about preparing kids for the workforce, high schools followed suit.

Unfortunately, the side effects have been fierce.

A philosophy professor writing under the pen name Hilarius Bookbinder here on Substack recently alerted us that many students at his regional employment-prep public university are graduating as functional illiterates:10

I’m not saying our students just prefer genre books or graphic novels or whatever. No, our average graduate literally could not read a serious adult novel cover-to-cover and understand what they read. They just couldn’t do it. They don’t have the desire to try, the vocabulary to grasp what they read, and most certainly not the attention span to finish. For them to sit down and try to read a book like The Overstory might as well be me attempting an Iron Man triathlon: much suffering with zero chance of success.

It’s easy to dismiss the charges, and many do when people like Bookbinder begin pointing to students’ addiction to phones. When that happens, the educators who sound alarms are often mercilessly attacked as old farts who are doing what fist shaking old farts have done for thousands of years: jeering at the youngest generations.

One of these fist shakers, Jonathan Haidt, of NYU-Stern, however, points to some numbers to support the concerns of the worried class of educators:

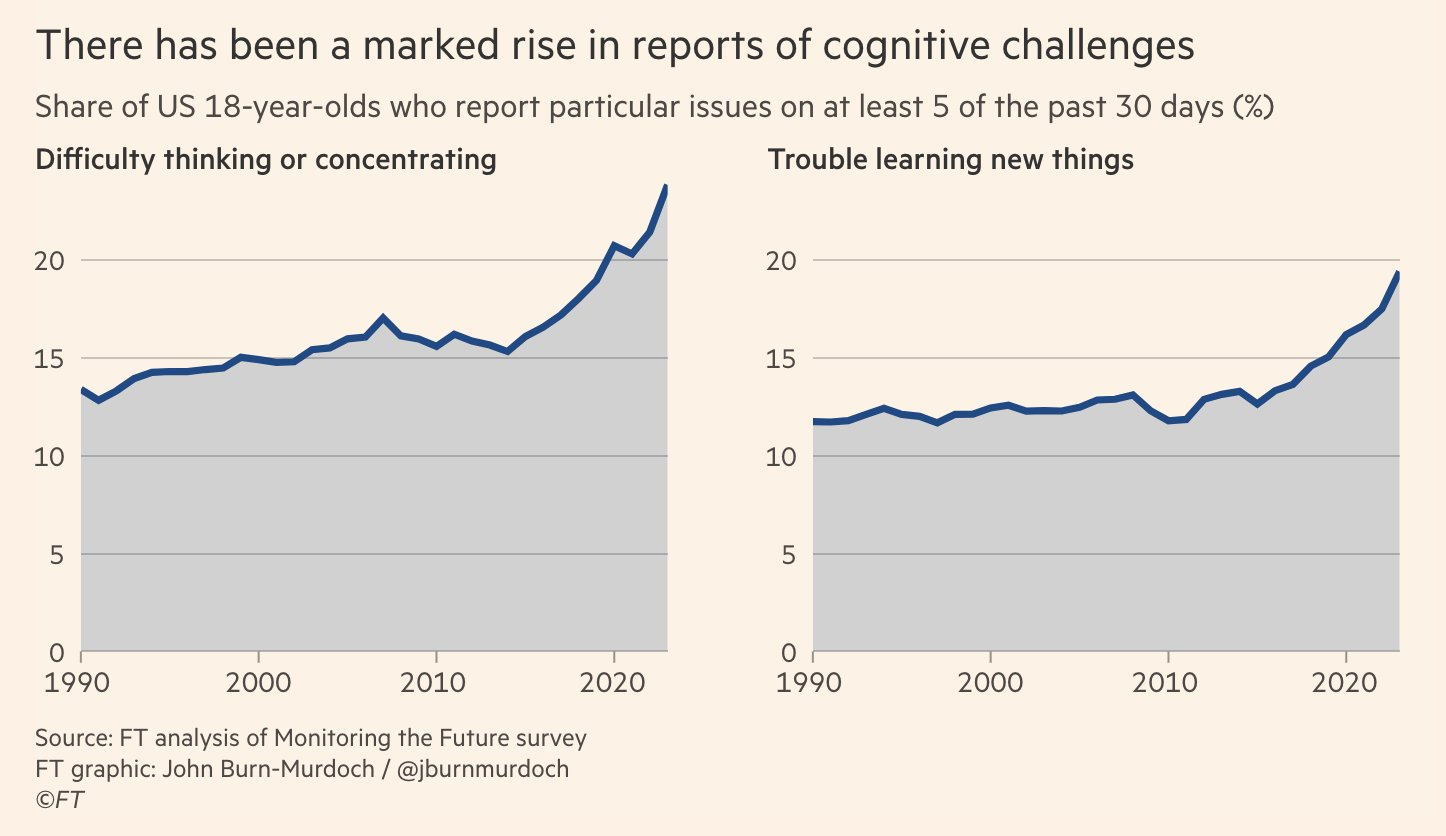

Haidt says recent studies by the University of Michigan specifically point to the addictive use of smartphones as a primary cause of the decline in young people’s cognitive thinking skills.11 The studies were conducted by a group sponsored by the University of Michigan regents called Monitoring the Future, which has been studying student trends since 1975.

Their main study has studied 120,000 students since its inception:12

The Monitoring the Future (MTF) Main study, also widely known for some years as the National High School Senior Survey, is a repeated series of surveys in which the same segments of the population (8th, 10th, and 12th graders; college students; and young adults) are presented with the same set of questions over a period of years to see how answers change over time.

Many educators believe that recent spikes in cognitive challenges are directly related to phone use. As one educator describes it:13

First of all the kids have no ability to be bored whatsoever. They live on their phones. And they’re just fed a constant stream of dopamine from the minute their eyes wake up in the morning until they go to sleep at night.

They just care about the next fix—because that’s how addicts operate. They have no long term plan, just short term needs.

They can’t get back to their phones fast enough.

More from Bookbinder:

They can’t sit in a seat for 50 minutes. Students routinely get up during a 50 minute class, sometimes just 15 minutes in, and leave the classroom. I’m supposed to believe that they suddenly, urgently need the toilet, but the reality is that they are going to look at their phones. They know I’ll call them out on it in class, so instead they walk out. I’ve even told them to plan ahead and pee before class, like you tell a small child before a road trip, but it has no effect. They can’t make it an hour without getting their phone fix.14

I know, I know, it all sounds like frustrated old fools raging at the sky. But real numbers are starting to creep in. Students are getting dumber. Many can’t read. The combination of a purposeful withdrawal of universities and high schools from the humanities and the onslaught of smartphones is creating what some are calling a zombie culture.15

I see the evidence here on Substack, too. It makes sense that most of my readers skew towards middle age and older. I don’t bother hiding that I’m older through my writing. And I’m happy they, and you, are here (no matter your age, of course).

But when I look at the comments on Substacks written by significantly younger people, I see the same thing: Lots of people closer to my age than the average university student’s age.

I think most of us, if we’re being honest, see the problem right in front of us all the time if we know young people. Phones, everywhere, all the time. The thing is, it’s not their fault any more than cigarette addiction was my parents’ fault.

Like cigarette companies, which spent years hiding data showing cigarettes were harmful, social media companies have begun to do the same. This graphic was buried by Meta, the owners of Instagram and Facebook, until it was leaked by the Wall Street Journal:16

Need more data? The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Will Bunch has some for you:17

Last year’s National Assessment of Education Progress found the percentage of eighth-graders with “below basic” reading skills (33%) was the highest in the exam’s 30-year history, and fourth-grade skills are also way down. And this trend was developing before the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted in-person schooling.

None of this even touches the AI dilemma, which Bookbinder points out is an extended attack on both literacy and cognitive thinking. AI, he says, is so prevalent that he and other educators have determined there is no way to fight it, so many have stopped trying to issue essay assignments. The students simply use ChatGPT to write the answers for them. Educators have no resources for policing that kind behavior.

Another clear association between cell phone use and education comes from a surprising place: prisons. Jonathan Jacobs18 runs a nonprofit that teaches music to kids in juvenile prisons. He notes that these kids, who have no access to cell phones, are engaged and excited to learn the music education curriculum that Jacobs’ nonprofit provides to young inmates in these facilities:

This kind of evidence establishes a clear argument: It’s not the kids’ fault that they’re all handed brain sucking devices at an early age.

“What can be done?” you might be asking, possibly through tears.

Like many things that seem intractable, some simple solutions exist:

Establish federal guidelines that require public schools to establish comprehensive reading and arithmetic skills. Forget about the rest. The rest will fall into place if the kids can all graduate from the public school system fluent in Dickens, Hemingway, and prime numbers.

Stop giving your nine-year-old kid a smartphone. Worried about school shootings? Buy them a flip phone and tell your congress critter to stop allowing the sale of automatic weapons of war.

That’s it.

The rest will take care of itself.

If you’re a writer, know that there are approximately 143 million Americans between 18 and 30 years old. There’s a solid niche of serious young readers in that group. My personal decision as a writer is not to dumb it down (some might fairly argue that much of my writing is already dumb enough — but I thumb my nose at thee, with glee!).

I’ll trust my readers to find subtleties in my work. I’ll continue to hope to attract readers who crave information and creativity. Hopefully, I can satisfy their demand for good prose. My niche doesn’t include people who can’t finish a book. Nothing personal against those people, but they won’t be interested in my Substack. They probably won’t be interested in yours, either. They may check you out for a bit, but they’ll get bored and leave.

Chances are, the majority of your readers aren’t in the 18-30 age range. But we can still speak to the millions of avid readers in that age group. Substack’s sudden lurch toward video seems to be yet more evidence that its owners expect the number of avid readers to dwindle as younger populations age.

It would help to know that Substack won’t respond by deteriorating into a video platform, or worse, promote video while feigning support for long-form writing. If it does, I, along with others, will find another place to nest.

Thanks for reading!

Footnotes

Most likely because I don’t know about them, not because I don’t like them.

Shut up, Grammarly. I’ll use “literally” if I want to. And “really,” too. Because I really own my own work. No, seriously, I actually do. You’re a nice spell check machine, Grammarly, but you’re also kind of stupid.

My dad was a heavy drinking car salesman, and my mom was, God rest her soul, a professional pill addict.

If you’re wondering how I survived the playgrounds, I assure you that I didn’t tell my classmates that when I came home from school I buried my nose into Dante’s Inferno.

Imagine a modern publishing company employing some of the many wonderful illustrators in this country to create a series of classics for kids to read. A fantasy, of course, in this world of late-stage capitalism. The real fantasy may be that kids would read them, but not if public school curricula rediscovered them.

Sadly, none remain.

Heer, Jeet. 2017. “The Post-Literate American Presidency.” The New Republic. September 23, 2017. https://newrepublic.com/article/144940/trump-tv-post-literate-american-presidency.

See what I did there?

See what I did there?

Bookbinder, Hilarius. 2025. “The Average College Student Today.” Substack.com. Scriptorium Philosophia. March 25, 2025. https://hilariusbookbinder.substack.com/p/the-average-college-student-today.

Bookbinder isn’t the first to call attention to student illiteracy. See:

Horowitch, Rose. 2024. “The Atlantic.” The Atlantic. theatlantic. October 2024. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/11/the-elite-college-students-who-cant-read-books/679945/.

Burn-Murdoch, John. 2025. “Have Humans Passed Peak Brain Power?” @FinancialTimes. Financial Times. March 14, 2025. https://www.ft.com/content/a8016c64-63b7-458b-a371-e0e1c54a13fc.

“About | Monitoring the Future.” n.d. Monitoringthefuture.org. https://monitoringthefuture.org/about/.

https://x.com/j00ny369T/status/1900357484545442119 (apologies for the Twitter link)

This might be a good time to remind you of my short story about a phone alert issued by the government that instructs everyone to kill themselves within thirty minutes:

Gioia, Ted. 2025. “What’s Happening to Students?” Honest-Broker.com. The Honest Broker. March 21, 2025. https://www.honest-broker.com/p/whats-happening-to-students.

Ibid, Gioia, Ted. 2025.

Bunch, Will. 2025. “Young People Won’t, or Can’t, Read a Book. Now Democracy Is Dying. Coincidence?” Https://Www.inquirer.com. The Philadelphia Inquirer. April 10, 2025. https://www.inquirer.com/opinion/student-book-reading-declines-20250410.html.

“Jonathan Jacobs - Pursuing His Passion from Music to Technology to Philantropy.” 2022. Authentic Leadership for Everyday People - Podcasting and Executive Coaching. April 25, 2022. https://authenticleadershipforeverydaypeople.com/podcast/jonathan-jacobs-passion-music-rawkstars/.

Substack was great platform that encouraged writing. Free unedited writing there are still great writers here but for me lately Substack seems to turning into another instagram if I want instagram then that’s where I’d be. I came here because I have met and interacted with great writers. Like minded writers who care about what they write about. Care about their country and most of care about humanity and I say to everyone I’ve subscribed to ❤️!!

You beat me to it…for the last several weeks, this has frustrated me. I see "Listen now!" or "Watch” and I shut down because I. DONT. HAVE. TIME. I want to read words because I can absorb them faster. Personally, I think doing the audio/video stuff is sort of lazy, unless you’re Acosta … and even then, I dont always have the time for him.

This was a great essay, as always. 👏👏👏👏👏